By Jason Barnard

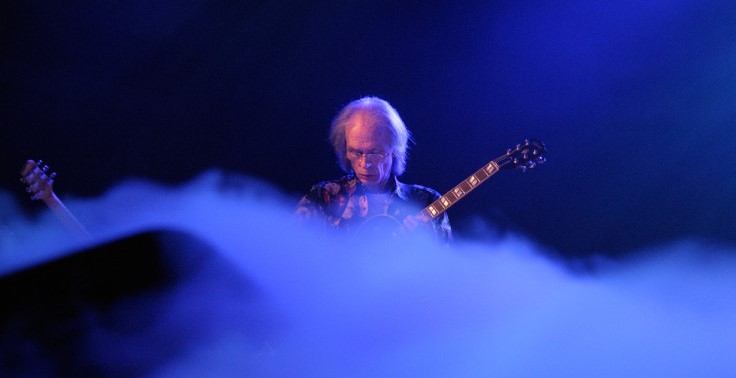

Steve Howe reflects on his illustrious music career spanning from the 1960s to the present day. A standout moment in his journey was the release of Tomorrow’s debut album, which has recently undergone a reimagining. Our conversation will explore the intricacies of the album’s creation, the technological advancements used to enhance the tracks, and the creative process driving the project. Alongside delving into Howe’s notable accomplishments with The Syndicats and in YES, we will also discuss his latest album with the group, Mirror To The Sky. This record boldly blends YES’s iconic sound with innovative elements, cementing its significance in their evolution.

Hello Steve. We last spoke in 2019 around the release of the New Frontier album by The Steve Howe Trio.

Oh yeah. OK. Thanks.

This time it’d be great to cover two aspects, things that kind of bookend new music. Firstly, the new version of the Tomorrow album and latterly it’d be great to catch up on YES.

Sure. We can do that.

Excellent. So, I’ve been listening to the new version of the Tomorrow album but it’s badged as being re-imagined. Can you tell us about what’s different with this new version?

Yeah, sure. Much like Giles Martin did with [The Beatles] Revolver, it was a process that I imagined could work. I got Keith [West] and Twink to agree to the idea. Basically, the album that we made in 1967, which came out in 1968 unfortunately, which was also a silly thing about it, it wasn’t really perceived as a psychedelic record and yet I knew that’s what the group was really heading into. So it’s a kind of a process. In other words the first thing we did was we requested the original mono mixes because they were the least available things of Tomorrow, because most of it was in this stereo format which was very unsatisfying and it was kind of tinpot. There were a lot of factors in it that were in the audio sense were missing. Anyway, I thought it would be quite easy to describe [he chuckles] so basically. like it says in the sleeve, I kind of re-imagined it so, in other words, I took the tracks into the technology and did minimal things to it. I mean some of it is virtually the same but some of it isn’t and the things that aren’t, particularly with ‘Revolution’. That song was a bit of a muddle what was going on in it – the different tempos and things like this – and there were gaps and all sorts of things so basically this reimagining was really like looking at the music and saying, well, What would be desirable to do this, to bring it into line with ‘My White Bicycle’? and things like that which were obviously purely psychedelic. So, basically, things were adjusted more. It wasn’t really mixed so much as things were adjusted and we were able to do a tremendous amount now with the mono mix. You can adjust the eq’s on individual instruments. You can adjust the balances if they’re a bit kind of crude and lots of them were. So, at times, the harmony vocals were too loud, sometimes something was too loud and the general chaotic feeling that I corrected. So by taking three tracks off the album ‘Mary somebody’s Dress Shop’ [‘Auntie Mary’s Dress Shop’] and these other kind of songs [‘Colonel Brown’ and ‘Shy Boy’] which weren’t really treated seriously by us at all, they weren’t developed at all. So, anyway, we took those three tracks off but there was room for other sort of hidden gems like the album opens with the alternative version of ‘Real Life Permanent Dream’ which was really just a live version done in the studio and that’s how we, more or less, how we played it on stage and I started the album with that. The very purpose that we titled it Permanent Dream and also I wanted to show the energy in the band.

Then we go into the further songs which all have a little bit of treatment. So, basically, all I’m doing is stylizing things as much as I can, developing, getting things in tune, in pitch. Some of the tracks were running at the wrong pitch and that affects my ears a lot because it doesn’t sound right until it’s in tune. So we ‘in tune’ things which corrected tempos which and then we brought down a guitar or brought up the drums or basically we reposition those instruments to be more pleasing and we were thorough and doing this to every track, wherever it needed it. It was a lot of fun to do this, to make the mono mix really a convincing medium for Tomorrow.

And ‘My White Bicycle’ – superb production. You’ve got backwards guitar there. You’ve got policeman’s whistle. In terms of Mark Wirtz’s production, how far have you moved away from that or is it more a case of the balance of how it came out?

We haven’t lost anything he did. All we’ve done is, to our ears, we’ve made it more listenable now. It was partly the stereo mixes that were originally available were the old style where the vocals were on the right side and the drums are on the other side and if you mono’d that it sounded something like the mono mix that we’ve got but, there again, people aren’t going to do that. So the stereo mixes were checked in mono to make sure they’re all right but in fact they’ve not been available so yeah ‘My White Bicycle’ is one of the ones that’s least treated although, of course, nobody’s really heard the mono for a while and also we put a slight bit of phasing on a couple of bits in it just to kind of simulate a little from the stereos. It was a rough time for stereo in 1967 when we were mixing it. [Editor’s note: This was the era when mono mixes for UK pop records were the norm and most of the effort was put into creating them. Singles were king in the UK and they were in mono, which was in keeping with the majority of domestic equipment, few people owning the more expensive stereo turntables. Indeed until the late 60s/early 70s stereo mixes were often an after thought in the studio as well as being rushed, often being left to recording engineers, rather than the producer, to complete – which was even the case with The Beatles and Sgt Pepper. The pop radio stations of the mid to late 60s (Radio Luxembourg, the pirates and then BBC Radio 1) were all mono and it wasn’t until 1973 that Radio 1 started regularly broadcasting in stereo.]

You’ve got ‘Claramont Lake’ [the B-side to ‘My White Bicycle’] on this new version as well and I recall reading that that was one of Frank Zappa’s favourites?

Yeah. That was a big surprise to me when we met Frank. He said to me, “Oh that’s a great solo on ‘Claramont Lake’.” It was surprising that he’d heard it and delighted that he liked it and it’s one of those little milestones in my career where somebody said something, like Georgie Fame said something about me on my second Syndicats record, where he said he liked the guitarist or something. So those things, they really are important. They’re lovely ingredients of warmth and encouragement and I guess much like when I showed up to work with Mark Wirtz the first time ever on a session when there wasn’t anybody there and I said, “Well, where is everybody?” and he said, “No. There’s just you.” I went Wow. Studio Two. EMI. Just me. And I was tracking up guitars and doing things. Basically those little things are tremendously important to an artist where they had that little bit of encouragement and you feed off that and you go with it. Of course, Tomorrow was kind of much more of a breakthrough for me in lots of respects. ‘My White Bicycle’ was almost a hit record and all these kind of things almost happened for us but I guess one could be thankful that, maybe, we weren’t destined to be successful then and maybe it would have been dangerous if we had been, but we were trying and anyway. [Steve chuckles]

Yeah. Because Tomorrow, on that psychedelic scene around the time of 1967, you were up there with many of your peers like Pink Floyd and Jimi Hendrix and I think there was one moment where you were asked to stand in for Syd Barrett, but it didn’t happen?

Yeah. That’s another true story. I was excited to think I was going to stand in and jam. Really, it would have been a jam, most probably, because it was going to be no rehearsal but I was rushed there and then, the very last minute, he showed up. So I just had to cool my heels. Another classic moment, earlier on, was when Chris Farlowe asked me to stand ~ I mean I’m just blabbering about all these great moments, now you got me started, but I got a call from Chris Farlowe and he said, “Can you stand in for Albert [Lee] tonight?” and I went Well, I’m not turning this down and it was one of the best nights I could remember in my early career, being picked up in an Aston Martin and rushed to Wolverhampton and actually rehearsed with the Thunderbirds and Chris and, so, these moments, they never go away, thank goodness.

And the experiences that you had in the 60s were superb grounding for your work in the 70s but The Syndicats, for example, you had some great singles like ‘Howling For My Baby’, but you worked with Joe Meek didn’t you?

Yeah. That was a Joe Meek band really. Well, we were a band. We managed to get an audition with Joe and, yeah, that was my first recording experience really. I kind of look up to Joe a bit because he also was quite encouraging. But also it was about realizing another important side of the business is actually getting on with people and if you don’t find a producer too intimidating then you can get on with him and then when he says, “Oh let’s overdub a solo” you’re in heaven. Oh, we’re gonna overdub, great, great. Joe was a hell of a character but he was my grounding along with the few other producers that I work with and basically the engineers as well, like on Tomorrow. Geoff Emerick was a fixture at EMI. He came with it. And that was really fantastic and the other guy, Peter Bown. I always watched engineers. The desk was a scary looking thing. It looked like it was like a spaceship. Of course, it wasn’t in any comparison, but the desk, Joe Meek and his tapes. He had the floor full of tape and he cut bits of tape out of things and sped things up. So, basically, what went on besides playing the guitar fortunately really interested me. It was something that I thought you would learn about and I guess I did.

After Tomorrow’s split you joined Bodast. Although Keith West was the producer you actually had a very young Ken Scott as engineer.

That’s right. Again, we were lucky to just find these guys. We were at Trident, I think, doing that and Ken was there. It’s a wonderful thing to rub shoulders with these people. Sometimes you don’t even know that you’re really rubbing shoulders with them until their name becomes apparent later and then you look back and think Wow, that was great. So it was marvellous to have their skills. Like Eddie Offord with YES, for the first five years, was really this go-to guy. The answer to the problems. We were supposedly producing YES as a band but we couldn’t have done it without Eddie. And the same with Keith when we did the Bodast album. In between, of course, I did some work with Keith on a few tracks which did eventually come out. It had some fascinating line-ups where Ronnie Wood was playing bass and Ainsley Dunbar was playing drums. So Keith was assembling, in between Tomorrow and Bodast, ideas for further recordings. So that’s always interested me. I guess Les Paul basically started all this really. He’s one of the best producers ever that the world’s ever had. If you listen to his work today it’s completely astounding that it could possibly sound that good and yet it was recorded on what we would call a pile of junk. I mean stuff, old tapes, and one of his first hits wasn’t even recorded on the 8-track machine that he was notorious for inventing [nicknamed ‘The Octopus’]. So there are some remarkable things. George Martin – remarkable. Phil Spector, I suppose. But also there’s an awful lot of producers who don’t get any credit and like, maybe, Ron Richards with The Hollies. So many of these key people who’ve done things for bands. So I guess I was always thinking You don’t get here on your own. I didn’t come out as like a solo singer or solo guitarist. Having always been in bands, I always fully appreciate what teamwork really is.

‘Nether Street’ which is a Bodast song, there’s a riff in that came back later in YES with ‘Würm’ [part of ‘Starship Trooper’ on The YES Album], so would you often reach back to licks or riffs or ideas that you had in many years before and dig into them?

Well, not if they’d been released but the thing about the Bodast album, it wasn’t released. I saw that music as canned, shelved possibly. And it could have been for forever. In fact if it hadn’t been for the fact that I was very moved in 1978 to hear the news that Clive Skinner – his real name was Clive Maldoon, he was sometimes credited as [Clive sang and played acoustic guitar on Bodast’s recordings] – had passed away and that got me to get together with Gary Langan and produce the mixes that we did and then release the album. When I got back to the album I thought Oh God, this is ‘Würm’. And there’s other bits of ‘Close To The Edge’ and all sorts of bits of songs in there. I don’t generally do that. It’s something most writers avoid is self-plagiarism, you could call it. But this was done under a different shelter. Obviously you can see how well it was developed by YES that I didn’t have any reservations but, yeah, I assumed that Bodast was dead and buried and I’d never hear from Tetragrammaton [the record company for whom Bodast recorded but which went out of business in 1970 prior to releasing this LP] again.

And some of the recent news is that the YES tour, which was European and UK dates for Relayer, have been put back another year. What’s your perspective on the Relayer album because obviously ‘The Gates of Delirium’ is such an ambitious and epic track. Where do you think that fits in under the YES albums?

Oh, well, right up there. 2018/2019 when we were playing ‘The Gates of Delirium’ and absolutely loving it and that was preparing us for doing Relayer, so that album’s right up there. If you look at the sequence ~ in fact I was in a black London cab the other day and the guy said to me, “Oh The YES Album. That’s the great YES album.” So, if you look the way that The YES Album was followed and superseded and improved on and you get to Close To The Hedge and [Tales from] Topographic Oceans and Relayer. I mean that’s a monumental chunk of work and it went on. Going For The One and particularly Drama I think is fantastic. So we had lots of hiatus in the 70s, no doubt about it. We were crazy, fanatical musos and rambling off on anything we wanted to. We were incredibly free and that’s the key to music. It must allow you to be free of restraint and oppression and things like this but, yeah, Relayer is a sensational record. It’s complex and maybe even overly adventurous.

One of my favourite solo tracks of yours is ‘Turbulence’ from just over 30 years now [the eponymous opening track to Steve’s third studio solo outing recorded in 1989 and released in 1991], the great Bill Bruford on drums.

Absolutely.

How would you approach your solo materials in areas like that as opposed to YES and similar collaborative projects?

Well, it’s interesting because, really, I quite like reviewing music. I once read a quote by George Harrison where he said he’s never listened to Beatles records. Once you made the record, he’d never listened to it. I don’t really think that could have been true but it certainly isn’t true of me. I like to, when I made a record, I don’t want to hear it for quite a while, maybe two to three months. That’s a really good break. After you just made it. I mean you spent maybe months making it or maybe years, with time over the years. Making the records is great and then not hearing them for a while, then try and appreciate what it is you’ve just done. So then years can pass. Quite recently I did a pretty big review where each night I pick one of my solos and listen to it and just sort of sat there and thought Well, yeah, I kind of like, yeah, I like this bit and Turbulence was forever interesting because there are times in the album Turbulence and the track epitomizes Turbulence, really, the album. Sounds were very dateable. In other words you can look back and you can see how you were thinking because of the time that you were in. So Beginnings (of Steve Howe) [released in 1975] I was just doing a lot of crazy jamboree, what I call my ‘jamboree’ albums, where there’s everything. I throw everything in. A bit of country, bit of rock, a few songs. It’s a kind of bizarre, almost crazy idea I had the way that that kind of hung together in my mind. So, when I listened back, I can see where I was coming from but I didn’t carry on making every album like that. I got into things like Spectrum [Steve’s instrumental album released in 2005 with a band that included his sons Virgil and Dylan as well as Rick Wakeman’s son, Oliver] and things that were much more defined as a direction. So, when I hear Turbulence, I leapt out from moving across my albums. This was a quite a techno sounding kind of album. The first couple were much more homely sounding, I think, in some respects, besides the orchestral work. But Turbulence, it’s not an anger but it was angular. It was kind of pushy and, of course, I had a nice bit of help from Billy Currie on the keyboards on that one but besides Bill Bruford but I think on that particular track it’s an organist who plays at actually St Paul’s Cathedral and he played some organ on there for me. His name slips my memory [Andrew Lucas]. I’m sorry.

Oh, no worries.

It’s somewhere. It is credited and he was a lovely chap. We just did that one session for me on a special organ. So that track was full. When I put the CD on and it went [mimics a plane taking off] and the plane started flying around, I always had a bit of fascination for sound effects and I guess that one was key. I had this record called A Nuclear Powered Submarine or something. I have sound effect records which were a bit out of the usual and I’ve still got them. I collected them. If I see something weird I go, What’s that? Oh, the sound of a nuclear submarine. Got to buy that. So that was the kind of crazy stuff I bought, as well as music from Tibet and all sorts of weird records. Just anything that wasn’t ordinary, wasn’t in the charts, I would most probably buy. But ‘Turbulence’ had this kind of [atmosphere], as an album as well. Later on there’s a hurdy-gurdy playing somewhere [on the track ‘Turbulence’] that we utilized. So there’s a lot of ambitious and also, when you look at ‘The Inner Battle’ and particularly, goodness me, there’s one track, about the third track [possibly track two ‘Hint Hint’], I’ve got multiple kind of riffs going and when Bill came in to play on it, I just kind of said to him, “Well here it is, but I don’t know what you do with this.” And he just he listened to it and he went, “Well. I think it’s changing from like 7/8 to like 11/8? or something.” I said, “I don’t know.” I play this stuff and sometimes I don’t even know really what time signature it’s in because I just keep playing the parts that I feel. So he went out there and he kept moving the downbeat one beat along every bar and this just did something wacky to the track. ‘The Inner Battle’ and, I don’t know what the other one was, but they were particularly carefree. But like ‘While Rome’s Burning’, he just laid back and very, very straight playing really from Bill but that doesn’t diminish when the fact that his drumming had like almost an elevation beats in it. There was a way that Bill – and he could still do it, I’m sure – but all of his drumming showed that incredible lightness of touch where he didn’t need to do a whole load of Buddy Rich breaks. All he would do would just be Bill Bruford and that was great. So that team on Turbulence was very, very exciting to work with and I guess that’s when I started to shine and craft my records more than I had the first two. I think that was my third record and, yeah, it was a lot of fun.

And, of course, it’s good to talk about the forthcoming YES album Mirror To The Sky and we’ve all heard the new single ‘Cut From the Stars’ that’s been really well received. It must be difficult given that now Alan’s sadly passed on, so how is it moving on from Alan to craft this new album?

Well it’s almost like, YES is a kind of bulldozer. When you look at the 70s and how often we’d change members and then we look at the 80s and how different that was then and then start to develop, so the way that we’ve managed to cope over the years, all different members have managed – not only me of course. Not only me being there but when other people – when I wasn’t there, is what I’m trying to say. So, when I wasn’t there, they still found ways of getting over the next hurdle. And they had a few hurdles in the 80s. A friend of mine tells me about the way they made those two albums and then the last album. YES get over problems. We continue because there is a sort of inner flame of YES that nobody holds. No one person holds it. It has to be a collective like kind of Olympic flame of YES. There has to be something going on even if I’m not there, even if so-and-so’s not there. So, basically, it’s a bit like a gauntlet that gets handed on to the next collective that is actually managing to get their heads around, not only playing retrospective YES music impeccably well, but also as we’ve shown, starting to demonstrate now with The Quest and now Mirror To The Sky, this band may be able to create relevant new music and I wasn’t fully convinced of that before in the latter 2010s. I wasn’t sure. I was always holding YES back saying, “Well, look, until we’ve got the songs, it’s no good really making a record too because what you need is songs.” So getting a good balance of songs and doing that but also, as I say, playing YES with the highest respect for the music and all the members that have been there in the performance. We missed doing the performance and we worked on our albums and we hoped to get more experience back. It is a great shame that we’ve, through various conjectury and uncomplimentary and unsatisfying developments through what we booked for 2020, just rotating this again was really hard and delaying it again was really hard, especially after we were out last year. So, it’s a curious sort of collapse. Part of that side of our ability to take on the tour that was planned for 2020, in 2023. So, really, we want to be able to do our best by knowing that what we’re doing is right and, by the time we got here this year, there were just so many things that were problematic. We will adjust that next year and come up with a new idea really for that because I feel taking Relayer along is a bit like taking Covid along. It’s become like, Oh no. Surely? Can we? Are we? Must we? No. We want to and the desire that we had in early 2020 when we’re all beavering away learning the detail of Relayer, not just the structure but actually all the notes. I was doing that. And we were all set to go off and play Relayer and I think we could have done it then. We could have done it in ’21. We could have done it in ’22 but, that’s what I mean, we kind of need to be able to book tours and adjust set lists accordingly to what we know is best for us and our audience at any given time.

And then to close, it’s clear that with the title track of Mirror To The Sky and there’s ‘Luminosity’ as well from that album that span over ten minutes, that the creative element of YES and the drive continues to flourish.

Well. Things don’t happen without hard work. This isn’t a carousel floating down some snow in Switzerland. YES has always been a band that was prepared to work on things very hard so, yeah, it is nice and it also good that gradually from The Quest and now Mirror, we’re starting to get a scale in our music that we like. We’re not ever trying, well, if anybody says, “Oh why don’t you do a 20 minute piece?” I just say, “Look. Can you just not say that? When we get a 20 minute piece, we’ll have one.” But we’re not trying to get that. What we’re trying to do is to work on our songs individually as really beautiful things that we can create together and get everybody involved. Everybody has great parts. We get all the balancing right. We’ve got all the textual qualities right. But we don’t want to lose that flame and we want to keep the emotion and the excitement that we’ve got in that. So that’s all part of the YES thing. But also, behind the scenes of course, it’s also an organization. It has to work structurally, contractually, within rules that are applied to us and everybody else in the world. Also we are carrying on a flag of a band. So, in lots of ways, we are still working with everybody who’s ever been in YES in one respect or another, in different degrees, with different arms out from different eras. I’m extremely proud to have come from The YES Album era and seen what I did in the 70s and then got back in ’95. It was much harder work in ’95 with Keys To Ascension and Open Your Eyes and, goodness me, there was just so many challenges that were greater in a way than the one when we had that new momentum – when Fragile came out and we were being welcomed into a more successful appreciation. So, continuing is exciting and it takes pace. It takes belief and strength. The bigger music we play kind of allows us to be more, not, ‘creative’ is a word that I try not to use. But to be more colourful, I suppose, and when you think about a great song like, let’s just say, ‘Penny Lane’. I mean that song is not like another Beatles song I can think of but nor is ‘I Am The Walrus’. So in a way The Beatles are totally the forerunners of this. Because, before that, bands did songs that all kind of sounded the same. It’s just a different song. There’s an organ and a guitar. The Beatles stopped doing that. They’d have a harmonica on this one, a Leslie guitar on this one. And basically I think that that’s the spirit of progressive music that was really started firmly by The Beatles in the sense of Psychedelia. And I’ve always said that Psychedelia developed and became Prog. So that’s my feelings about, like you say, YES, doing new music and also that we are, in a way, an incarnation of what YES needs to be and can be. And that’s the thing. ‘Need’ is one word but, yes, this is the YES that can exist and we’re very pleased.

Fantastic. It’s a lovely way to tie things up given that we started in the 60s with Tomorrow, peers of The Beatles, and it’s a pleasure as always Steve. I wish you all the best with the release of Tomorrow and the new YES album.

All right Jason. It’s been nice to talk to you. Nice questions. Very thoughtful. Bye.

Further information

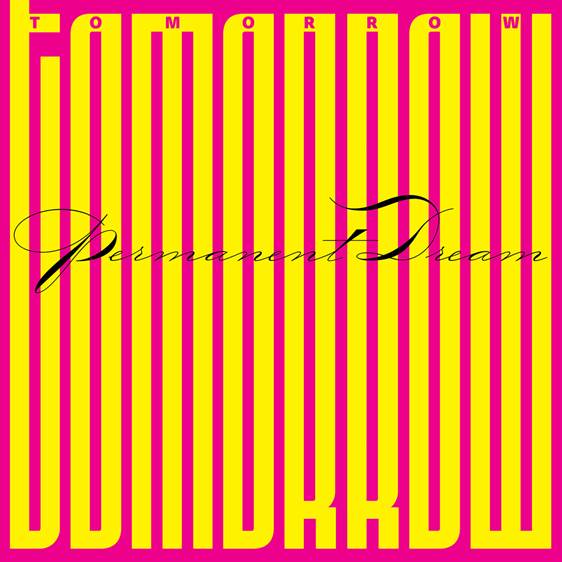

‘Tomorrow: Permanent Dream’ is released on 28 April 2023: CD, Black vinyl, Violet vinyl

YES’s new album ‘Mirror To The Sky’ is released on 19 May 2023: YES Official, Burning Shed

An audio podcast of this interview is due to be released by early May 2023.

Acknowledgements

Transcript and extra research provided by Nigel Davis.

Copyright © Jason Barnard, 2023. All Rights Reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the author.