By Dominic Picksley

Just one of many bands to have grabbed a small slice of the 60s action, The Summer Set are now a mere footnote in the annals of UK pop. Despite possessing swashbuckling surf-styled harmonies, mod sensibilities and a freakbeat undertone, the group were never destined to emerge from the shadows and their tale is one of missed opportunities, bad luck and personality clashes that ultimately brought about their demise.

Remembered as one of the UK’s leading ‘surf’ groups, which in swinging mid-60s London may have turned off the scene’s hipsters, they were a favourite of Keith Moon and rubbed shoulders with some of the best in the business. But the passage of time has not been kind to The Summer Set and their legacy has been widely forgotten.

They deserve recognition, though, for their ‘cult classic’ 1966 single and while they did not leave behind a huge body of work, they nonetheless stood out from the crowd due to their triumvirate amalgamation of surf, mod and freakbeat, which resulted in some unique-sounding records that have stood the test of time.

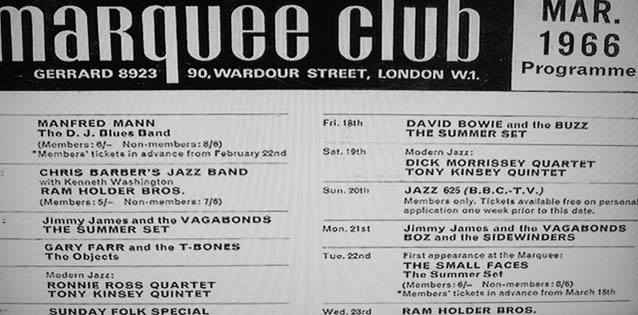

Chart action and big-time fame eluded the short-lived Summer Set, despite being mainstays of the famous Marquee club, having a regular slot on a BBC pop show, performing in front of thousands at a huge rock festival and taking inspiration from The Beach Boys. Two of their members, though, rose out of the ashes of the surf group to hit the big time in the 70s, with Cliff Richard and the Eurovision Song Contest key stop-off points in the history of the band.

The Summer Set story, the full warts-and-all version, is told by Dominic Picksley and he is helped along the way by former band members Rocky Browne, Vic Gillam and Dave Green…

The seedlings of The Summer Set were planted in late 1960 when Lewes Grammar School pupil Martin Jenner formed The Javelins in the Newhaven area of Sussex, with his brother Guy, while fellow guitarist Dave Green, also a pupil at the same educational establishment, started his musical career in earnest with skiffle band The Vampires.

Both groups made a name for themselves on the local scene for a couple of years before future Cyan Three frontman George Sims quit The Javelins – Martin then approached Dave about becoming his group’s new bassist. Dave’s Vampires bandmate John Bright also made the switch to pound the skins with The Javelins.

With this new line-up in place, The Javelins – an instrumental combo – continued to play youth clubs until early 1963 when Martin and Dave went along to a gig at the Newhaven Labour Club, to watch a band called Johnny Sultan and The Sheikhs, who had a saxophonist, Vic Gillam, along with guitarist/keyboardist Brian Cornwell, the brother of actress Judy Cornwell – who is best known for playing Daisy, the ‘working class’ sister of Hyacinth Bucket in the BBC sitcom Keeping Up Appearances.

“We had been performing for some time before we got together with a singer [Peter Senior] who had just got back from Germany and we started playing at Newhaven in 1963,” said Vic. “We were playing one day when a couple of guitarists came up and had a chat with us and we got together with them.”

Martin and Dave disbanded The Javelins to form a new band with Vic, Brian, drummer Mike Mendoza and singer Peter Senior.

Dave explained the get together in his excellent autobiographical book, The Wonder Years: “They (Johnny Sultan and The Sheikhs) were splitting up, but Peter was forming a new rock band and was looking for more suitable musicians. That was it. We convinced him that we we were just what he was looking for.”

Count Downe & The Zeros were born, a name conjured up by Peter’s dad, who also became their manager. Dave added: “Within days we’d been measured up for stage outfits – white jeans and dark blue blazers, with a great big zero on the breast pocket. We looked like the Dave Clark Five on a bad night.”

In June 1963, drummer Mendoza left and was replaced by Geordie Carl Simmons, also an accomplished pianist and songwriter, who had cut his teeth playing in bands across France and Germany.

After a few weeks, Peter’s dad stepped down as the group’s head honcho and in came new manager Michael Hartz, while the band were beginning to make a real name for themselves on the south coast, playing at venues such as The Green Topper, in Bognor, Cliftonville Hall, in Hove, and Brighton’s Corn Exchange.

Later that same year, Brighton Kemptown Conservative MP David James used the band as part of his campaign for the forthcoming 1964 General Election. The group were promised a contract to write the music for a Conservative party film being made, but James lost his seat and the deal was reneged on. The band took a letter of protest to10 Downing Street and received an apology in the post, but nothing more.

Around this time the group acquired the services of a publicist, through one of Brian’s contacts. Gordon Thomas, who just happened to be married to local journalist and future Radio One legend Annie Nightingale, and set about boosting the profile of the group. He managed to get them extensive coverage in the local papers, while he also organised for them to play at Goldstone Ground, the home of Brighton & Hove Albion FC, during the half-time interval, in front of 15,000 fans on Boxing Day. The Downing Street protest was also his idea.

Within a few weeks they signed their first record deal and it was all thanks to a gig at the Regency Ballroom, in Brighton, prompted by another Thomas idea. The band’s biggest show to date, they performed in front of a horde of screaming girls that saw the local press coin the phrase ‘Zeromania’. But as Dave explained, all was not as it seemed: “The papers never knew our manager had spent all of the gig money paying an assortment of girls from our local coffee bar to pretend to go frantic, tearing their hair out and generally over-reacting.”

But it was this ‘very warm reception’ that persuaded Ember (an independent label set up in 1959 by Jeffrey Kruger) to offer them a contract and the band duly signed up. Kruger said at the time: “I have looked for three years for the right group and here they are, right on my doorstep. Their southern sound is fresh and original, they’re not copying anybody.”

After a couple of local TV appearances and a gig at the Brighton Hippodrome, where they shared the bill with Helen Shapiro and Sabrina, Count Downe & The Zeros went into the studio and recorded their first single, Hello My Angel, on February 17, 1964.

Hello My Angel, written by local water-skiing instructor Gary Gordon, was a slightly up-tempo ballad that had a definite early 60s feel to it. It was described by the New Musical Express in April 1964 as the ‘Southern Sound’, a moniker that failed to catch on. The B-side was Don’t Shed A Tear, co-written by drummer Simmons and their manager Hartz, who were both clearly influenced by Elvis Presley.

[tubepress video=yEkz-UF-mu8]

“Gary Gordon was a local guy who used to write songs and we recorded quite a few of his,” said Vic.

The song did not go down well with certain members of the group, including Dave who said: “It was a sort of tuneless ballad that not even Norway would enter for the Eurovision Song Contest. We knew it wasn’t destined to be a hit and to make matters worse we discovered that the only airplays it would get was on the Ember show on Radio Luxembourg, a programme what went out once a week at 12.30am.”

Other tracks penned by Gordon, but which went unreleased at the time were I Don’t Mean It (which suggested the group’s early leanings towards harmony pop), One Broken Heart and You’re My Girl, which can be found on the Ember compilation Hello My Angel – Ember Sixties Pop Volume 3.

In checking the original tapes for this collection, Ember unearthed a series of unissued tracks from the era, which suggested some burgeoning songwriting capabilities within the group. Peter co-wrote Always On My Mind and Rolling Stone, Dave came up with How Can This Be True, while Carl also pitched in with If I Find A Word and Baby Come Back To Me.

Hello My Angel failed to make an impression on the charts, but undeterred the band ploughed on and acquired a residency at the Long Bar, a pub next door to the Brighton Ice Stadium. It was there that they were spotted by Barry Langford, the producer and director of BBC2 pop music show The Beat Room, which aired between July 1964 and January 1965. Langford invited the group – minus Brian Cornwell, who had been ousted by this time – to become the new resident band, taking over from Wayne Gibson and The Dynamics.

They appeared once a week on The Beat Room, receiving £15 a week, and backed numerous famous acts such as Smokey Robinson, Paul Anka and The Righteous Brothers, and according to Vic: “The Beat Room was the most fantastic thing we ever did.

“One of the best things I was ever involved in was on the New Year’s Eve show where we performed with the Graham Bond Organisation, who had Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker at that time. They augmented us with three saxes, three trumpets and three trombones. I was on one of the saxes and Martin was on guitar. We backed PJ Proby and it was just brilliant.

“We also played with the Harry Rabinowitz Orchestrations and we backed Julie Rogers [most well known for her 1964 number three hit The Wedding] on the same show.”

Late in 1964, a change was on the cards when they acquired a new boss, theatrical agent Leonard Urry, who had seemingly ‘bought’ the group from Hartz. He suggested a name change and overnight they became Peter and The Headlines.

The newly-named band then signed with Decca and in September they recorded the single Don’t Cry Little Girl, backed with It Was Love, both written by local songwriter Gordon.

That record failed to chart, but the group went back into the studio two months later and cut the single Tears And Kisses, a song penned by Stanley Gelber. This was their strongest effort to date, while the B-side was a track co-written by Martin and Dave called I’ve Got My Reasons. By now, their harmonies were starting to emerge, but the 45 again did not catch the attention of the record-buying public.

“It was a great song,” said Vic of Tears And Kisses, “but for some reason it was just wasn’t a hit. The singles were quite well promoted as we were on The Beat Room at the time, but they never took off, although the harmony leanings were now beginning to come through.”

The group had their Eureka moment while on The Beat Room and decided, after playing alongside a certain quintet from California, that a change in musical direction and style was to be implemented.

“We were mad on The Beach Boys,” admitted Vic. “When I Get Around came out, Martin bought Shut Down Volume II and round about the same time, The Four Seasons released Rag Doll and they inspired us to start playing around with four-part harmonies. That was the four of us without the singer, who didn’t want to know.

“They [The Beach Boys] used our equipment on the show to promote When I Grow Up (To Be A Man). They were really nice guys. They were great days back then.”

Dave added: “The Beach Boys were an inspiration to us. They were perfect. Their five-part harmonies were a dream to listen to. Their sound set us on a different course.”

Out went the old and in came the new, with Beach Boys and Jan & Dean covers the order of the day for the band as they went about promoting themselves as a ‘surf’ band, a move that certainly set them apart from their UK peers.

After The Beat Room had run its course, Urry got the group a gig at a night club in the West End called The 400 Club, next door to the Odeon in Leicester Square, a club which he had shares in.

“It was the poshest clientele you could get,” said Vic. “Princess Margaret and John Paul Getty – he was in there two or three nights a week. There was a big band there and us – we used to do half-an-hour on and half-an-hour off. It was great as we used to go to Ronnie Scott’s every night.”

Urry also arranged for the group to play at society balls in and around the Mayfair area of London, while they also became the band of choice for rich clients at their country houses, although it left Dave feeling “rather embarrassed to call myself a musician at this point”.

Despite their recent good fortune and regular work, all was not well within the band and Peter and The Headlines began to splinter. First to go was singer Peter Senior and the group placed an ad in Melody Maker in an attempt to recruit a pianist as the The 400 Club required the band to play music from the 40s ands 50s. A new vocalist was deemed unnecessary as most of the group were by now competent singers. After being inundated with replies, the group eventually found their man.

“We got in a keyboard player called Les Humphries,” said Vic. “He was in a Marines band. Then we got in a young drummer and things started to look up for us again.”

Les had joined the British Navy music corps at a young age, where he learnt to play the piano, clarinet, saxophone and trumpet. He later joined the Marines as a military musician and played across the world in places such as Japan, Singapore, India, Vietnam and Australia. He eventually applied for a discharge as a bandmaster sergeant, before successfully auditioning for Peter and The Headlines.

He was a few years older then the rest of the band members, but according to Dave he was “a professional musician, but amateur human being”. The two of them were never going to get along.

By now the group were a fully-fledged surf music outfit, with Humphries’ strong falsetto rounding off their four-part harmony sound, although the former Marine was going to become as much a millstone round the group’s neck as he was a vital cog of their collective engine.

Carl Simmons then quit in order to return to Brighton and a young drummer called Brian Johnson took over his stool, before the group knocked The 400 Club on the head after passing an audition at the famous Marquee Club, where they signed on as the UK’s foremost surfing group.

“We began at The 400 Club in January [1965] and by the October we had got in with a few people at The Marquee and signed a management deal with Marquee Artists – we toured and worked at The Marquee as the second group to The Who – we were always Keith Moon’s favourite group and he wanted to manage us,” said Vic.

“We also started doing sessions, backing other artists’ demos, including Paul Jones, things like that in their small studio. Then we started doing Radio London Club on a Saturday afternoon, ‘Live from The Marquee‘.”

Harold Pendleton, the owner of The Marquee, became the group’s next manager, and paid the band the customary £15 a week and not before too long, they ditched the name Peter and The Headlines, for something more in keeping with their style of music and they became The Summer Set, a name thought of by bassist Dave.

More group movement then occurred, with Brian Johnson leaving, as Vic explains: “The drummer we had, he was very good, but he didn’t want to be a pop musician, he wanted a regular job, so he left.

“Rocky Browne was at that time with The Boz People [formerly The Tea Time Four]. When they broke up, Ian McLagan went with The Small Faces and Rocky came with us.”

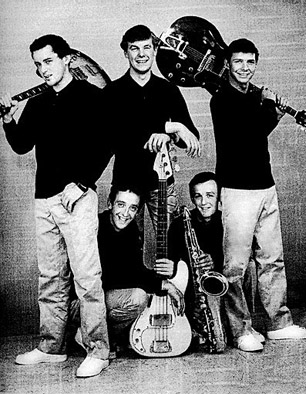

Drummer Rocky had spent four years playing with The Tea Time Four/Boz People, as he explained: “I was considered to be the consummate mod and referred to as a ‘loon’, a trendy word for a stylish airhead, whatever that was supposed to be. I had experienced a thrilling rollercoaster ride with The Boz People – we were four college friends who decided to play music rather than follow the career paths our fathers had planned for us.”

The Boz People were another of the groups who were regular performers at The Marquee, so The Summer Set did not have a difficult job in finding a new drummer.

“As a weekly performer with Boz and the boys, the Summer Set management team – who were part of The Marquee set-up – did not have to look too far for a replacement as I was on the spot, so to speak, but I auditioned all the time,” said Rocky.

Rocky’s move to The Summer Set may well not have happened if he had taken up the offer to play with a band that had invited him for an audition, none other than The Artwoods no less.

“I was told to go to Hounslow and I played in this garage, with Art Wood and Jon Lord on a huge Hammond organ,” Rocky explained. “But I told my agent I didn’t really fancy it and that was that. And bugger me, within a year Jon Lord was playing with Deep Purple. I didn’t regret it though.”

Rocky’s switch from the jazz-infused Boz People to the surf-music style of The Summer Set did not sit easy with him in his early days with the group: “I had come from a blues/funk/jazz style band using delicate time and rhythm signatures to a heads-on four beats in a bar, on your marks, get set, go, surfing band.

“At first I hated the style of music, and Les was a ‘bastard’ to work with – very demanding in an aggressive style. But I gradually got into the groove and started to enjoy the band. Les, I guess, was the musical influence behind the material we played – mainly covers of The Beach Boys, Jan & Dean, and other US west coast musicos – but he did compose a few songs that we recorded along the way. He was easily influenced by the success of other bands and I recall he was smitten by The Move.

“Harold Pendleton was allegedly very impressed with the band when he saw us for the first time and thought us to be a viable alternative to the blues/jazz/rock genre bands that were currently performing at the club.”

During late 1965 and due to the burgeoning number of US-styled harmony acts springing up in the UK, the Marquee introduced ‘Surfin’ Nights’ as part of their weekly repertoire, although the idea while popular at its inception never really caught on.

“The Marquee basically did that for us,” explained Vic. “There were also Tony Rivers & The Castaways, Robb Storme & The Whispers and The Majority, who used to perform on these nights.”

Dave remembered the night playing with Tony Rivers and his group: “It had been hyped in the press and the place was packed. Taking a set each, we sang and played our hearts out and then at the end of the evening, dripping with sweat and the crowd yelling for more, we joined forces and sang I Get Around. It was sheer magic and one of the most talked about gigs I’ve ever done.”

Surf music historian Kingsley Abbott remembers seeing The Summer Set on the same bill as Tony Rivers & The Castaways. He said: “There were only four members on stage at the time, but they were great. I remember thinking they had a more rounded sound than Tony Rivers’ band. Tony and their other lead singer tended to swap about a bit between songs, but all the guys in The Summer Set sang and I was very impressed by them.”

Read the second part of Dominic Picksley’s feature on The Summer Set here: