Legendary engineer Phill Brown looks back on his incredible career in an extensive interview with Jason Barnard. Phill shares his experiences as a young tape operator on sessions for Jimi Hendrix, Rolling Stones, Small Faces, and Traffic at Olympic Sound Studios; to engineering for Mott the Hoople, Led Zeppelin, Nilsson, Bob Marley and Steve Winwood.

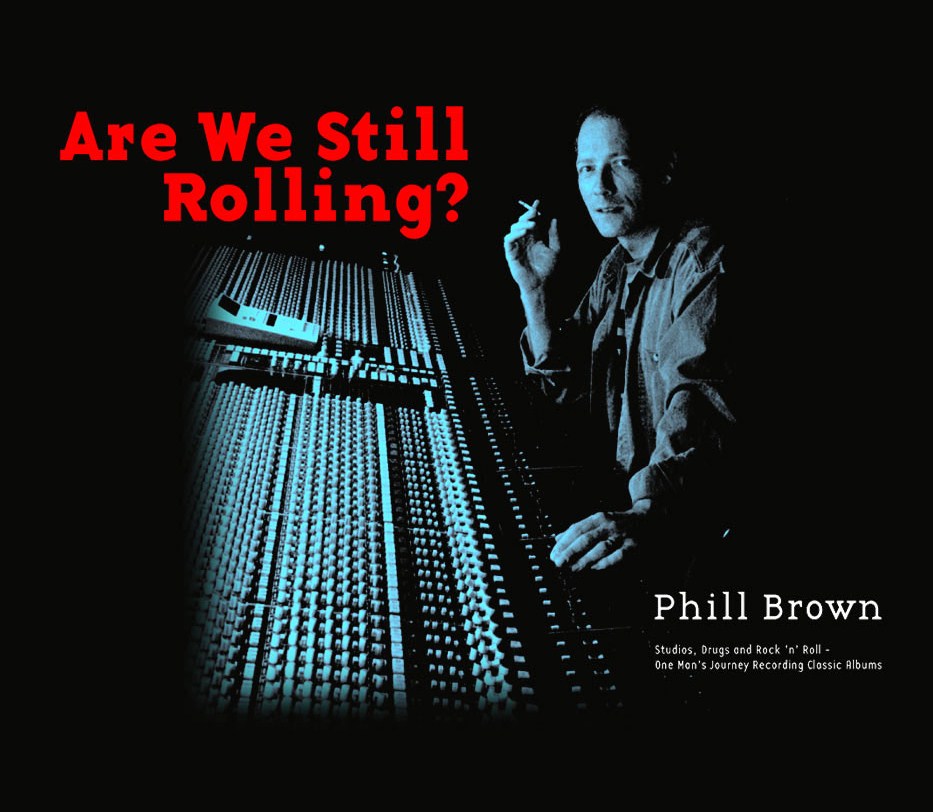

You have a book out detailing your time in the music industry: ‘Are We Still Rolling?: Studios, Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll – One Man’s Journey Recording Classic Albums’. Almost straight away you were involved in recording some fantastic tracks. You were the tape operator for Jimi Hendrix’s ‘All Along The Watchtower’ for example.

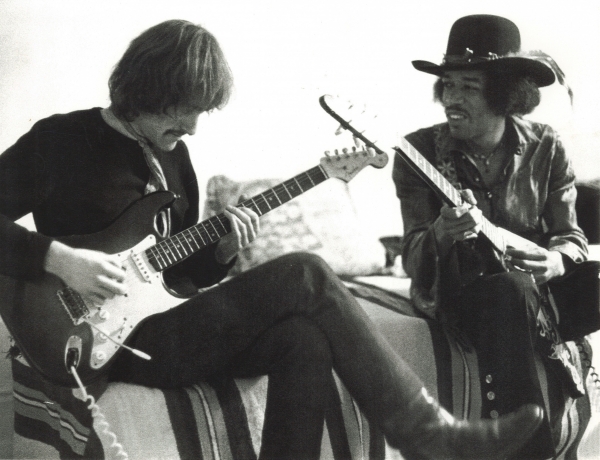

That’s right. I was 16 and had been working at Olympic for about three months. We were packing up a session one night when we got a phone call from Eddie Kramer saying that they were at a party and was the studio free as they had an idea. They came down so I was there by default. They cut the track, Dave Mason played acoustic guitar and Mitch Mitchell was on drums. I heard later that the bass player, Noel Redding, said that he didn’t think it would be worth going to the studio. So he never turned up and Hendrix played bass. It was amazing.

Dave Mason and Jimi Hendrix (photo from davemasonmusic.com)

Yes, it must have been an incredible time with all those amazing artists coming into the studio day after day.

Olympic Studios was so popular in that 67, 68, 69 period. I was lucky to get a job as a tape op and got to train under Glyn Johns, Eddie Kramer, Vic Smith and the various people working there at the time. It was a fantastic education. This was in the days of four track as well, unlike today where you have unlimited tracks. These records were made on four or eight track machines.

So you were bouncing the tracks off each other.

Yes, you tended to fill up four tracks. With the Hendrix thing he’d fill up a track with bass, one with drums on a track, and two with acoustic guitars. That was bounced to another four track into a mono so you’d have three more tracks to carry on working. It seems crazy in today’s technology but they made some amazing records back then.

You also worked with The Small Faces on their ‘Ogden’s Nut Gone Flake’ album.

Again as a tape op. It was around March 68 and it was the first album that done to the new eight track Ampex machine. I taped op with Glynn most of the things he brought in for a year. The Small Faces were one of my all time favourite bands anyway but they were just such great people to work with. They were just so funny, a lot of humour and a kind of chaos. It was a great way to work.

You mentioned in ‘Are We Still Rolling’ that you used every available space, including the toilets.

In that era and in the 70s the rooms became even deader because they wanted to remove leakage. So if you wanted something in a different space you had to record it there as you had no plugins to give you that. We had an echo plate and tape delay so if you wanted something to be live we often recorded in corridors or stairwells, things like that. We used the toilet for “Lazy Sunday” to do overdubs because it just sounded very live and bathroomy.

What talent, especially Steve Marriott and Ronnie Lane.

Marriott is just one of the underrated singers of this country, such a great singer, such a force. He seems to have been slightly forgotten over the years. They were a brilliant band.

You worked in that period on ‘Beggars Banquet’ by The Rolling Stones. One of the highlights is ‘Sympathy For The Devil’ and it’s interesting that you’ve said that it went through many different styles.

I think that album took six weeks to make, which in that era was an incredibly long time. Typically you were making albums in a few days or a week. So to spend six weeks was unusual.

‘Sympathy For The Devil’ started off more like a country song. Slowly over the days, they came back to the song in amongst recording other songs to finally come up with the version you hear on the record. But a lot of time was spent on that album, plus we had a film crew there as well that added to the chaos.

You mentioned in the book that there was a fire as well.

Yes, they put up extra lights because the studio was always pretty dark. A bulb blew which caught light to the diffusing paper, which then caught light to the hessian covers on the ceiling. It turned into a fairly big fire which went right into the roof in the end and left a large gaping hole to the sky. And it was the end of the album.

What a way to end. You also worked with Traffic and you’ve talked about the party atmosphere recording the Traffic album.

Like the Stones there were always a lot of people around those sessions beside the band. There’d be friends who’d come and hang out with them. The first time I worked with Traffic was for the ‘Dear Mr Fantasy’ track in November 67 and they had a lot of their friends hanging out at the studio, sitting around the walls. It was a very relaxed atmosphere, very much like being in your living room. I think they liked to get a more down home vibe when they were working.

They were one of my favourite bands and I especially loved their second album. And Steve Winwood, what a force. He was already a success from the Spencer Davis Group when he was 14/15. When I worked with him in Traffic he was 18 and I was 17.

It’s incredible to think how young you were at the time.

From an engineering side there were no courses. The job didn’t really exist so you had to go into a studio and train. People started pretty young, I started with Chris Kimsey and Keith Harwood. We were all about 17/18. I was engineering by the time I was 19.

And you don’t have a musical background.

No, I don’t. I played drums briefly when I was 14/15 but once I went to into the studio all my social life stopped and I just drifted from playing. The one thing I regret is that I don’t have a more musical background.

You didn’t have a seamless transition to Island Records. You went over to Canada.

I left Olympic and my brother Terry Brown who had built Morgan Studios emigrated to Canada. I followed him and built the first 16 track studio over there in 69. The studio was in Toronto and we built and ran it for about a year. I came home to visit my parents and had heard about this studio being built in Notting Hill Gate for Island. So I called in to see the place and say “Hi”. There was a whole load of ex Olympic guys there and they offered me a job which was a tricky one. But I accepted it and didn’t go back to Canada.

And were Mott The Hoople one of your early projects as house engineer?

They were. I joined initially as a junior engineer and did all the outside artists that weren’t on Island. That’s how I got to work with Jeff Beck and Led Zeppelin.

But this was one of the first things I did for Island. I knew a couple of the band and their producer, Guy Stevens. He was an A&R guy at Island above the studio so I got involved with Mott The Hoople that way. Pretty crazy sessions, actually. They were a pretty wild bunch. Guy Stevens was a real character unlike a modern producer who would want decorum and control. He was an anarchist in a way. The sessions were very different, even with what I was used to at Olympic.

And as a new engineer that must have quite a test.

It was such a steep learning curve. Today if travel to all the world’s studios you’ll probably end up on an SSL. Back then every studio had their own desk. At Island we had Helios desks which was similar to Olympic. Trident had their own, Air had Neve. So everyone had different sounding desks. Getting used to the desk was probably my biggest learning curve in 70-71.

That was the period where Mott The Hoople didn’t have much commercial success but they still did some great tracks like ‘Waterlow’ from the Wildlife album you worked on.

‘All The Young Dudes’ is the track they’ll be most remembered for but they were a great live band. I don’t know what happened to them in the end; they probably imploded. They were a great band of the day.

Another great band you engineered was Led Zeppelin. You’ve said the recording process for ‘Stairway To Heaven’ wasn’t as seamless as you’d guess from the outside.

Yes. In hindsight I’ve worked with Robert Plant a couple of times and he’s explained more about the way Jimmy used to work. He used to improvise guitar solos and then work out the bits he liked and then slowly construct a solo. But no one explained this to me at the time.

So we were in Studio 2 at Island, Jimmy sitting next to me with his guitar plugged through the walls into an amp. He just said ‘Again’ and we’d record. ‘Again’ was pretty much all he said for three days. But no one explained why we were working the way we were. It’s sad in some ways because to have worked on ‘Stairway To Heaven’ should be a great moment, but the actual process was really difficult. Not just the technical side but having their manager Peter Grant there. Jimmy Page was going through a fairly dark time; I think it was a combination of Alastair Crowley and heroin addiction. It wasn’t easy by any means and the atmosphere was very tense.

And you only recorded a couple of tracks.

That’s right. They worked in various studios but tended to work at a house in the West Country where they recorded all the drum tracks and most of the parts. So when it came to Basing Street I was there to do the acoustic and electric guitars and flutes on ‘Stairway To Heaven’. Then I worked on ‘Four Sticks’. Then they moved to their usual location and probably their usual engineer, who I think at the time was Andy Johns who did most of their recordings after Glyn.

And they were long days.

All studio life back then was. You would do 12 hours minimum and often 18 hour days. We just lived for work. We loved it, it was fantastic. Even when we weren’t working we’d often hang out at Island as there was so much going on and musicians calling by. But they were long days, very intense.

Another artist you worked with is Nilsson. You’ve talked about the producer reducing Harry to tears during the recording of ‘Without You’.

The producer, Richard Perry, was an interesting character. He was very successful but quite hard in the way dealt with most people. He had quite a strict attitude. They had been recording at Trident and the engineer had a car crash so they were looking for somewhere else to go. So they came to Basing Street and I worked on the Nilsson Schmilsson album. We did the vocals in the control room, which was unusual, so we put a mic and wore headphones. Because of that the singer can’t hide behind screens or have any space. He’s right there in front of you.

It was just Richard’s manner really. I had arguments with him as well, which was bold as I was only 21. He was tricky. Part way through yet another vocal take Harry just broke down. Whether it was the way Richard was treating him or whether it was to do with the song itself I don’t really know. But it appeared to be Richard upsetting him.

The production on ‘Without You’ is fantastic.

Yes, it’s a beautiful album generally. And that song, there’s very little on it in some ways. It was all manually mixed and it was probably one of the hardest tracks I had mixed up to that point in my career. It took us eight to ten hours to mix one song which was unheard of in those days. You’d probably mix something in about three hours because when you’re doing it manually there’s a limit to how many times you can keep running it through and trying get a mix. After a while you peak.

‘Without You’ was my first proper number one record as well. Over the years it’s taken on a slightly darker aspect with me and my wife. At the time we’d just got married, had a number one hit and it was like ‘This is brilliant. What a great song.’ Then later the two guys from Badfinger that wrote it committed suicide. Then Mariah Carey butchered a version. Slowly over the last 20 years I’ve drifted from that song. Every time it comes on the radio you think ‘Oh, here it comes again.’ But it is an amazing song and it is a great album.

You spent such a long time recording in that period. There’s a lovely bit in the book where in November 74 you had your first day off for months and you got a call that morning that said “You’re recording Pink Floyd at Wembley tonight.”

Penny Hansen who run Basing Street had a tough job being a studio booker. You only had four engineers and four assistants and had to kind of juggle it around. But it was my first day off in a long, long time. I think partly it was that she phoned up and said ‘Right. You’re doing this’, without any kind of discussion. Floyd back then was a pretty big scale of set up. Nothing ever’s straight ahead.

Had I known I was doing the gig I would have been out at Wembley the day before, as early as I could be to get a grip. But because the engineer that was doing it moved to the PA set up and I was brought in; I only had time to drive to London, get a cab to Wembley to be there for the sound check and you’re up and running. It was really nerve wracking from my point of view. Also the main thing was that I wanted a day off. I wanted to sleep and see my wife. So I was pretty pissed off that I’d been brought in.

So you had very little time to prepare.

None at all really. Brian Humphries was going to do the live recording but ended up doing the PA, set up a large amount of it. I was walking in to someone else’s set up anyway. Fortunately it all went very smoothly. Penny had said “Brian’s set it up just watch the levels” and made it sound like it would be easy. But in fact it did turn out easy, every thing had been set up well. The Floyd crew were a bit like the army moving in, extremely good at what they do. So it was 85% sorted before I even got there.

Was that show for the radio?

Yes, it was live for the BBC. It sat around in the stores after it had been used. Then Floyd got a lot of albums out and remixed them a few years ago. It was one of those recordings that they remixed and put out as an album.

It is a really good recording. Moving on, you must have had a fantastic time recording with Robert Palmer. Wasn’t the ‘Sneakin’ Sally Through The Alley’ album recorded at your home?

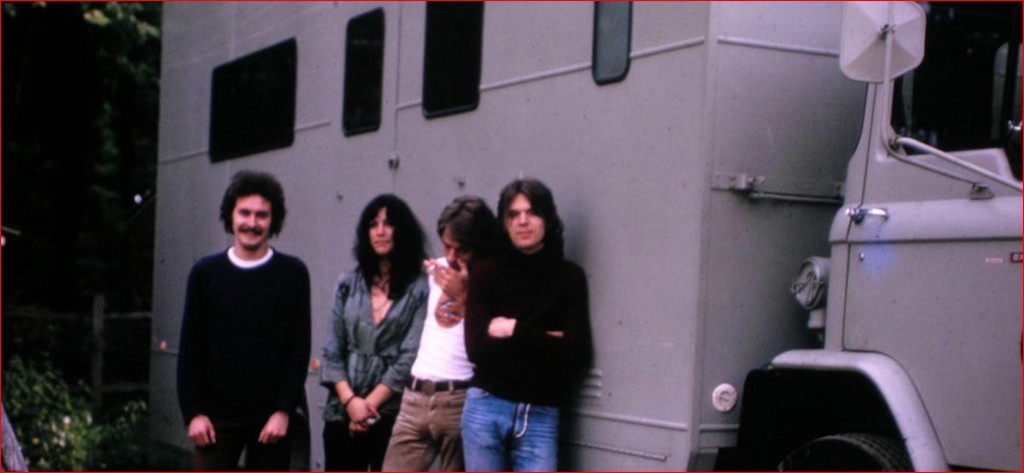

A lot of the overdubs were. After a few years mostly doing outside artists I slowly got more and more involved with Island. From around 74 onwards I did a large amount for Island. The basic tracks had been recorded with The Meters in New Orleans on 16 track and had gone back to Basing Street where we were going to be doing overdubs. We were using the Island mobile outside the new Island offices in St Peter’s Square. Our plan was to do the rehearsal there and use the truck. But we had so many interruptions we decided to just get in the truck and just drive it to my house.

So we turned up at my house with Steve Smith the producer, Robert, Jody the percussionist, as well as Ray Doyle who run the truck and his assistant. So we recorded a lot in the house and outside in the countryside, churches and all kind of things in this local area. It was a brilliant way to work and Robert and I ended up working on four albums together. He was a good mate.

Robert Palmer (second from the right) and Phill Brown (far right) in front of the Island mobile (photo used with kind permission of Phill Brown from phillbrown.net)

You worked with him a lot in the 70s.

I did four albums and a couple live things. ‘Sneakin’ Sally’ which was the first solo album is somewhat underrated. It was a great album at the time, did really well in America but he always got really bad press in the UK for some reason. I don’t think they ever really got it. They were such exciting albums to work on. Whether it was The Meters, then Little Feat or James Jamerson and the Motown guys, they were just our musician heroes that we working with. They were all in different parts of America, different studios; very different studios to England, Muscle Shoals in New Orleans, LA and New York. It was fantastic experience, a brilliant time.

You recorded the definite version of Bob Marley and The Wailers ‘No Woman No Cry’ live at the Lyceum Theatre. The sound of that live album is incredible; it’s up there with ‘Live At Leeds’.

Great. We did actually record over two nights at the Lyceum but the first night was chaos. The audience invaded the stage so we didn’t get much we could use from the first night. The second day we positioned the mics slightly differently and had better security. So the gig all comes from the second night. Once you’ve set up and done your soundcheck, once a live show starts it is whatever it is. There’s not an awful lot you can do. So the recording went pretty smoothly in the truck. But what surprises me more and more as time goes on is that we mixed the whole album in six hours. I just find that remarkable because if you give me all those tapes today I’d probably want three days, get it into Pro Tools and get it just right. Back then it was manual mixing.

We set up ‘Trenchtown Rock’ first which was a track from the middle of the concert. While I was setting up the mix, Blackwell just kept yelling for more audience. The whole band were there, they were spliffing and dancing around. When we got it to the point of where how he heard it he said ‘Great let’s go back to the top of the concert.’ We didn’t even put down ‘Trenchtown Rock’. We went back to the start of the concert and ran the reels off, almost like front of house. Just manually riding things as you went. Then a couple of cross fades, editing it together. In six hours the whole thing’s ready. You could buy it within a week or two of the gig. It was such an exciting period.

You worked with The Wailers in the studio too.

I worked on the Burnin’ album which was the second album. It was the studio one that came out before the live album on tracks like “I Shot The Sheriff” and things like that. So I had done a bit of studio work with them. Most of the tracks had been recorded on an eight track in Trenchtown in Jamaica. Then Blackwell brought it all to London and we copied the eight track to sixteen tracks and overdubbed people like Rabbit and various instruments to try and make it a little bit more commercial. We also sped up the machine which sped up the songs. When you do that you can get away with the music but the vocals always sound weird so we redid Bob’s vocal to the new speed and mixed that.

There was actually a big article written at the time. Somebody had got hold of the originals, timed it all and obviously worked out that it had been sped up. They were querying why you would do that to reggae music. It was obvious Blackwell was trying to get to a wider audience. Instead of roots reggae it was more accessible.

So I’d done a bit of studio work, then the live album. Because of the new studios over in St Peters Square from then on Bob Marley did most of his stuff there or over in America.

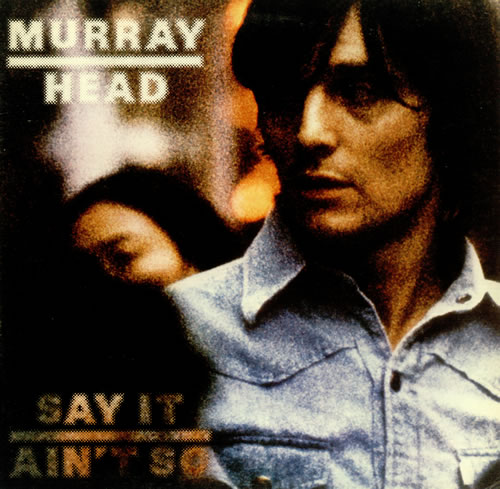

Murray Head is a very underrated artist that you’ve worked with quite a lot.

I met him in 71 while he did his first solo album ‘Nigel Lived’. It was a kind of concept album and very involved with the technology of the time. But he’d had success in Jesus Christ Superstar and West End type shows. He was also an actor and been in ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ which was a big film of the day with Glenda Jackson. So we worked together on his first solo album which was for CBS. That all went to the wall, it wasn’t successful and he then signed to Island. But I worked with Murray on and off for a good 10 years and I even did something for him about three years ago.

I think he’s got a beautiful voice. He’s another underrated singer of this country. I think a lot of people get confused as to whether he’s an actor who can sing or if he’s a singer who acts. It’s always a bit difficult spreading yourself into two different areas because people don’t quite get it. I did a lot of touring with him in the 80s as well when I went on the road with him. He was a good mate.

We did a demo of ‘Say It Ain’t So Jo’ with Murray at his flat in Fulham and the demo is absolutely stunning. Not good enough to release but just beautifully put together. So we then went in, Paul Samwell-Smith produced the Island album. Great song. Probably the biggest hit he had, huge in France where he’s a bit of a hero. But over here I don’t think that many people know of him.

You worked with the Sensational Alex Harvey Band in the latter part of their career recording the album ‘SAHB Stories’. It included including the hit ‘Boston Tea Party’ which was one of their last great moments. What were they like in this period? I understand this was when things started to get more difficult for the group.

Well, they were a great bunch of guys and good musicians. I guess one has to remember that the 70s was a very intense drug decade. There was always a lot of spliff and then cocaine started to float around.

Alex was a pretty serious character. He drank a lot and smoked a lot and generally was a little crazy. But he was brilliant as well, such an inventive guy. The sessions again had a lot of humour, a lot of drugs and a lot of great music.

You have a great story from the Stomo Yamashta project which featured Stevie Winwood. The band were playing and you let the tape roll even though you knew you were running out.

We were working on ‘Crossing The Line’ and the album when it’s finished is pretty much a continuous piece. But obviously we recorded them in individual songs. We’d been working on this track a while, recording it and going over it. This was a take where instead of stopping where they would normally stop, Klaus Shulze the moog player just kicked into the next song and everyone just picked up on it. So we are now into the next song and I didn’t have enough tape left to record this whole six minute track. We used to have 16 track and 24 track. We were working on 24 track on Stomu so we fired up the other 16 track machine at a certain point because we only had Dolby’s that you could only use for either machine we switched to other machine and captured the rest of the song. We then had to copy it back to 24 and edit it together. Part of the reason was that it just happened like that. I didn’t really want to push the button down. It was the who’s who of people in the big bands of the time, Steve Winwood, Mike Schrieve, Al DiMeola. There was some amazing people. Rather than just go on the talkback and say ‘Sorry guys, we are just running out of tape.’ I just let it run and tried to work out an alternative because I thought they might also stop as the song wasn’t the one we were trying to record. But sods law, both of them became the master. So with a copy and an edit it all worked but it was fairly nerve racking.

A year later you worked on Steve Winwood’s first solo album, there’s some great tracks on that album like ‘Vacant Chair’.

‘Vacant Chair’ was one of my favourites. Steve hadn’t really worked and had taken time out after Spencer Davis and Traffic. He was 23 or 24 and burnt out so just took time out. The first solo album he did was the first one he had done in about three years apart from the All Stars which was a live project. We started in a studio built in an old school house in Chipping Norton. Brilliant, very low key, great musicians but very subdued sessions in a way because Steve is not a party animal. He’s a pretty serious musician. We recorded enough tracks for an album and then Chris Blackwell came down to Chipping Norton to have a listen. You’ve got to remember that it was the the first thing Steve had done in three years. Chris said ‘This is fantastic you should record it all again with Andy Newmark and Willie Weeks.’ They were a rhythm section. We went back to Basing Street and the trio recorded the album.

‘Vacant Chair’ is actually the only one that survived from the Chipping Norton sessions. The bass player on that was wonderful Alan Spenner who died some time ago. It has the chorus in African which is ‘Only the dead weeps the dead.’

You worked on John Martyn’s 1977 album ‘One World’. I understand the recording process involved playing the songs repeatedly over quite a long period.

Yes, it was Chris Blackwell’s idea to go out and work with Robert Palmer with a mobile studio. He said that he thought it would be great to get John out of the house, use the mobile and record there as opposed to using studios. I think part of it was so we’d know where John was, it would be easier to control him. We set up with John in a 15 by 20 size room and we fed his guitar out through a PA system across the lake because Blackwell’s house was surrounded by a disused gravel pit.

John would just pick one of his songs and just play. Sometimes on ‘Small Hours’ it would be the length of a reel of tape. We were working at 15 IPS so it would be 30 minutes. If we had something we’d keep it but if not we’d go back to the top and run it again. Certain tracks were edited and constructed out of the free form performances. Amazing guy to work with, especially back then. With the sound of the guitar coming off the water around Chris’ house it was pretty magical. It sounds like nothing else really.

Yes, it’s a very unique sound.

The ‘One World’ title track is lyrically fantastic. I still love that album.

Going into the 1980s you worked with Talk Talk and you recorded the ‘Spirit of Eden’ album. That’s an album that’s really rated by musicians. I read that it was seven months work over eleven months.

We were in the studio for seven or eight months spread over almost a year. The 80s was a strange decade for me. To get going I found all the new technology, the FSL’s and early digital, I didn’t really get on with any of it too well. So for the first part of the 80s I felt a bit like a fish out of water. Because of the punk thing had happened a lot of the guys that I’d been working with had all moved on in one way or another, their careers had ended. The 80s was tough. So to get to work with Talk Talk was brilliant as I’d loved ‘The Colour of Spring’, it was the best album of 85. So I got involved with Tim Freeze-Greene and Mark Hollis for ‘Spirit of Eden’ which at the time was considered a failure by the record label. It got very little publicity. But over the last 25 years it’s continued to gain fans.

You recorded a choir for ‘I Believe In You’.

We were working with improvisation so that’s why it took so long. Nothing was planned. They’d come in and play and we’d edit. Once we had the tracks pretty much finished musically we’d do the vocals. We brought in a 25 piece adult choir to sing the ‘Hallelujah’, it was stunning, absolutely beautiful. But the next day when Mark came in we listened to it he said it sounded like The Adams Singers. Most people don’t know the The Adams Singers but they did easy listening albums in the 60s and 70s. It was ‘The Adams Singers Sing Stereo’, those kind of things, all middle of the road. So he said ‘Erase it’. In those days we did erase a huge amount of what we recorded but to erase a choir seemed quite extreme. A, because it had cost quite a lot of money to do and B, I thought it sounded beautiful. But we got it erased and the plan was to use some young boys. But because it was nearly Christmas we couldn’t do that. So we had to take time out and then we did it with I think six, twelve year olds that had that amazing sound.

Moving into the 90s you worked with Kristin Hersh. ‘Your Ghost’ had Michael Stipe on backing vocals.

It was. We working out in Rhode Island in a converted stable, in fact as was behind a studio as it was still used as a stable. This guy, Steve Rizzo, had put in some gear which was basic but very nice. So we recorded a whole album there, probably within two weeks. It was pretty fast, mainly acoustic guitar, vocals and the odd bit of cello. On that particular track she wanted to get Michael Stipe. I think he wasn’t prepared to go up to Rhode Island and we didn’t have the budget to go to him. We sent the tape to him, this was way before Pro Tools. So we sent him a quarter inch mix of the song. He recorded his vocals and bounced them onto a quarter inch tape back. So we then had to spin in and sync up his vocal to her vocal. It took a bit of trial and error for an hour or two but it worked.

Kristin was a very interesting character. I worked with her after that with her main band, The Throwing Muses. But I just love that song. The whole album was beautiful, great songs and vocals.

A few years later you got involved with Dido at the very start of her career.

Well I met her before her career. She had a day job and was Rollo’s younger sister. I worked with Rollo quite a bit from 97 with Faithless and Skinny. Some projects completely disappeared and others that were quite successful. I just remember one day Rollo, turning mainly to the Faithless musicians and saying ‘My kid sister has some songs she wants to put down. Would you guys be willing to do a few days? I can’t pay you what you normally get. So we did the album. It took about six weeks. It was great fun. It was still on analogue, it was very fast. There’s a great humour on that album and English quirkiness. So it all fun to do. No one would guess it would go on to sell 12 million records. It was the biggest success out of Rollo’s camp. Completely unexpected.

You then worked with Robert Plant again. This time recording his first solo album in nearly 10 years. You mentioned in ‘Are We Still Rolling?’ that he has a secrecy clause. What if anything can you share!

I had worked with him on and off a couple of times before that. I worked on ’29 Palms’ which was produced by Chris Hughes. But I thought he was completely the wrong choice as he was trying to make Robert into a pop act. It was never going to work. When I teamed up with him around 2000 for the ‘Dreamland’ album he knew I was writing the book at the time. We did talk a lot about the old days and the madness of Zeppelin, the death of his son, all kind of things came up. When he sent me through the production contract it had a clause in it that said I basically wasn’t able to write about it like that. I think it was because he knew I was writing a book and wanted some sort of control over what was and wasn’t said.

I still have a lot of respect for the guy. It’s brilliant how recreated himself over the last 15 to 20 years, making great records. He’s got a great band, Alison Kraus, the guy has really proved that their is more to him than Zeppelin. In contrast it’s quite sad Jimmy Page is still working on remastering Zeppelin and hasn’t really moved on.

You can really see ‘Dreamland’ as the start of that process to kick start his career.

He got the best reviews he had had for that album since Led Zeppelin. It’s a really good album. I have a personal grudge on it. We recorded at RAK at an API desk to tape. Our rough mixes from that sounded incredible. We then went to mix it in a computerised studio with an FSL desk. I could never get the same sound from as I had from the API with these roughs. So to me it’s always slightly disappointing as I know it could sound better.

You worked with Beth Gibbons and Rustin Man for the ‘Out of Season’ album. Rustin Man being Paul Webb from Talk Talk.

If you think the Talk Talk albums took a long time with a year in the studio, Beth Gibbons’ album took nearly three years. But it wasn’t in the studio all the time obviously. We’d do a week in the studio to record initially the rhythm section, drums, guitars, keyboards. As time went on horns and strings and so on. So we’d do a week’s recording and Paul and Beth would go home with their Pro Tools units and edit, kind of degrade sounds and mess around. We then go back into the studio and do some more recording, then disappear for a month or two. So it took a long time to make it that way. But it’s a beautiful album. I wish they’d do another one. Paul Webb, apart from being the bass player in Talk Talk has produced a couple of records in the last 15 years. But also seems to have disappeared from the music scene. All those guys, Lee, Mark and Paul have a pretty low profile. I’m not sure if they are still in music.

Jason

For the podcast you chose Midnight Choir and their track ‘Requiem’. I didn’t know much about the band but when I heard it sounded really lovely, with the strings it’s quite emotional.

Paul’s? got a beautiful voice. Chris Eckmann in Seattle has a band called The Walkabouts but he produces other things. He got me involved because of ‘Spirit of Eden’ to work with a Norwegian band called Midnight Choir. We’ve made four or five albums with them and won a Norwegian Grammy for our first album with them. Brilliant band, again imploded. Very few people outside Norway has heard of them. I love the singer and the songs; the simplicity of the way they made records. The tie up is that we got Tim Freeze-Green to do the string arrangements. They loved Talk Talk so we had Lee Harris playing drums and Tim doing the strings. But it was done very fast, those albums were made in three or four weeks, they weren’t long projects.

Getting us almost up to date you worked with a band still going from strength to strength, Bombay Bicycle Club on their second album, ‘Flaws’.

When John Martyn died they were involved with 10 other artists in putting together a tribute to him by recording John’s songs. I got involved because they thought it would be a nice tie up as I’d worked with him. So I first worked with them on an acoustic track about a year before we did ‘Flaws’. I think they really liked this new acoustic approach that they had so they did a whole album mostly recorded at Jack’s flat in Crouch End. It was done on a very basic home recording set up. He brought me in to mix it. We mixed the whole album in about four days, very fast and straight ahead. Tight budgets of course, like everything these days. But it was just a very different album. I love the acoustic side of that band as much as the indie electric. Great guys, talented and very young. When a I worked on that Jack was only 19 years old. They remind me of Laura Marlin, because I worked with her and she was about 16 years old. They are just young people wise beyond their years. But I really like Bombay Bicycle Club, cool little band.

You’ve recently worked with Mark Nevin who I’ve featured a lot on The Strange Brew. The sound of his album ‘Beautiful Guitars’ is really lovely.

Great. Because Mark was paying for everything on this album we worked very fast. It was a brilliant bunch of musicians, we would do three songs a day. Mark would then go home, edit, play extra guitars and do the vocals. We’d go back to the studio to do strings or brass. My main involvement was to record the basic tracks and to mix. We originally mixed at the Music Box which in Kentish Town. We were half way through mixing as we could only mix certain tracks. While we taking the break the studio got sold so we couldn’t go back. So we went to Brick Row which was the old Pink Floyd studio in Wandsworth to mix the next batch of mixes. Mark loved the sound of it, I think it was old Neve desk, that that we then remixed the ones we had done at Music Box. Again, the whole album was done in a short amount of time. He’s such a great songwriter, such great fun to work with. A lovely guy, looks after everyone well, great bunch of musicians, great songs. I’ve worked with him on and off, I think, for the last 20 years. This is the third of his four solo albums I’ve worked on. Not long after Fairground Attraction folded we went and recorded some tracks down at Chipping Norton in the mid 90s. Since then I’ve done a lot of his recordings because he only does an album every three years.

He’s done some fantastic records.

This is one of the best albums he’s done.

Yes, it’s been really well received. Taking us up to date but looking back you’ve worked with Arthur Brown in recent years.

It is like bookends because I met this guy back in 68 at Olympic when he was doing the original Crazy World of Arthur Brown ‘Fire’ poem and all of that. And although I didn’t see him for many years, over the last 20 years I’ve been back working with him, doing bits and pieces. I’ve done a couple of albums that have been slightly quirky. ‘Zim Zam Zim’ is in the same league as those original 68 recordings. It has a great vibe, great songs. He’s singing really well for someone who’s in their mid 70s. I just love the guy. He’s a real one off hippy. That’s why he lives in a yurt in Lewes and has no money but he always tries to push the boundaries. Every time he phones up to do something I’m always there.

It’s been really fantastic to speak to you. I was taken by the last section of ‘Are We Still Rolling?’ that says ‘Sound engineers don’t die they just fade out.’

(laughs) I do feel a bit that way. The technology and the way the business has changed now. Engineers are not valued in the same way now because everybody can record at home. All the musicians I know have home set ups, home studios. A lot of the great studios in London have closed down. The job of an engineer through the 70s and 80s, that’s not as relevant today. It’s a totally different approach. I do just think they fade away.

It’s definitely getting to point where I only want to work on things or people that I like. I will hang in there for this year.

Phill’s excellent autobiography “Are We Still Rolling?: Studios, Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll – One Man’s Journey Recording Classic Albums” (including a free pdf of the first chapter) is available via tapeop.com.

Copyright © Jason Barnard and Phill Brown 2015/2022. All Rights Reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced without the permission of the authors.