For those in the know, Martin Newell is one of the great English songwriters. He has produced records under a number of guises, most notably through The Cleaners From Venus. Their first burst of releases began in the early 1980s and had just a small cult following mainly due to Martin’s DIY approach and refusal to engage with the music industry.

However the world has finally caught up to his records in the internet age and the quality of Martin’s songs is now indisputable. The past few years have seen a big re-release campaign of his work with The Cleaners, solo records as well as an excellent new album out under The Cleaners From Venus moniker.

Martin speaks to Jason Barnard about the 60s pop that shaped his teen years and the unique career he’s forged; from mid-70s glam, surviving the 80s, 90s success and current renewal.

Martin speaks to Jason Barnard about the 60s pop that shaped his teen years and the unique career he’s forged; from mid-70s glam, surviving the 80s, 90s success and current renewal.

Martin, you have a great new album out ‘Return to Bohemia’.

Thank you. I’m glad people like it and it seems people do. I knew that it would be good as I made this album after I briefly died last year. I woke up one morning and had this mystery fit. It was probably due to fatigue and a stomach upset that caused me to have a potassium shortage. Basically I shorted out for a few minutes and woke up in hospital with a neurosurgeon looking at me saying ‘You’ve had a serious non-epileptic fit.’ I thought I have to get an album out to be proud of. I think I was subconsciously making an album just in case I wouldn’t make another one.

When I heard about your health troubles it brought me back to a track from your album ‘The Spirit Cage’.

‘My Funeral’. Well there’s been a lot of death around me this past year. I’ve been to five funerals in as many months. The first one was my mum’s. I just got out of hospital after my second eye operation and my mum died. I just got to the point where I just got inured to it. I thought ‘Hang on a minute. I better sing and dance and paint the walls.’ I reassessed things. I was becoming a grumpy old git until I briefly left the planet. There’s nothing wrong with me except a little high blood pressure. I casually cycle 16 miles round the countryside.

Let’s go back to your formative years. I’ve read you spent time abroad.

It must have been in September or October of ‘64 that I was shipped out to Singapore, very unhappy English boy with short back and sides, for the best part of two years. England had turned from black and white into Day-Glo. That was the last track I heard and took in my head with me from England to the far east. The Zombies ‘Leave Me Be’ was the last song I heard before going and it sums up black and white mid 1960s autumn for me.

So when you came back I assume you listened to the bands of the mid 60s like the Small Faces, Move and so on.

Yes, every man jack of them. They are my music influences. Tony Hicks, Allan Clarke and Graham Nash of The Hollies. Graham Gouldman is discernable in every era. He was writing with Captain Sensible and he left on his helicopter when I arrived on my bicycle. I missed him by half an hour. There’s a golden section in British songwriting between the summer of 1964 and the summer of 1968. That’s it. There’s great examples of whimsicality and genuinely great songwriting. Timeless, wonderful stuff. And although I don’t try and rewrite things I think ‘This is the form that I would like my songwriting to be in.’ It takes place in about three minutes, it begins and ends well and there’s a good chunk in the middle! There’s no dicking around putting effects on. You write a song before you go in the studio and it sounds good with whatever instrument you’ve written it on.

Fritz Fryer from The Four Pennies told me that once. He was an A&R man at Chrysalis or somewhere like that. I was 17 years old and he had me in his office. I didn’t even have to give him a tape. He just said ‘OK, what have you got?’ and I played him these songs. He said ‘You’re on the right track.’ If a song’s going to sound good it will sound good with one instrument and one voice. You should go with that.’ And I’ve struck with that my whole life. Everything after that is the easy bit really.

Did you start rebelling in your teen years?

Yes, it was not rebelling but it was my most troublesome years. I got home from my washing up job. I’d given up ideas for a career. I was 17 and I was paid just enough for my debauchery. Back to the house I was kind of squatting in with a mate of mine. He passed me a cigarette that I can only describe as quite long in shape. He put this thing on the Dansette and said ‘Right. Smoke that and listen to this.’ It was The Pink Fairies ‘Do It’ and I’ve never stopped listening to it. That track is the blueprint for punk. Certainly you’d get Captain Sensible of The Dammed to admit it. I reckon if you’d take that track to John Lydon and said What do you reckon to that Johnny?’. He’d probably say ‘Yes, I was aware.’ The only thing was that they made that in February of ‘71 and punk didn’t start picking itself up to mid 76. It was a great thing when you were 18 years old and didn’t want the checked shirt mellow stuff.

A few years later you had your first forays into the music industry with Plod, or The Mighty Plod. You were glam rockers weren’t you?

Yeah. When glam rock came along like when Mick Jagger once said ‘Generally an Englishman doesn’t have to be asked twice to put on make-up and a dress’. So off we went like a load of plumbers in bacofoil [laughs]. Dressed up playing in these pubs and clubs where half the time you had girls screaming at us and the rest of the time we were chased down the road by people who thought we were homosexuals and thought we needed to be beaten up. Honestly it was the best time of my life playing the great working class playgrounds of East Anglia. Leeds is one of the few other places we played in. We played the Fforde Grene twice, and The Staging Post.

Apparently, Johnny Cash played Fforde Grene.

It was big, like a Working Mans Club. It looked like a pub but it was a Tardis, just on the corner getting down in Harehills.

Rough area.

It wasn’t a piece of cake then. You went down that slope and went round the corner. The landlord was a bit of a roughhouse as well. A bunch of old Teds got up on the stage and danced with us. This wasn’t recreationist. This was proper old money Teds from the first time around . They would have been 40 and we were all skinny boys in late teens early 20s. So they got on stage and said [adopts Yorkshire accent] ‘Can you play Rock and Roll? You better fucking play it son or you will be fucking dead!’.

You recorded too.

I wrote a song called ‘Neo City’ because I thought it’s got to be futuristic. Before punk happened I thought that you’d had wearing greycoats and beards and can’t go back to the sixties. So I thought you had to go space age. You’d go to a machine and get your bacon and egg pill. All the usual things, the jet packs. My idea of the future was taken from The Jetsons. ‘Neo City’ was about that love had become an old-fashioned thing. You’d just meet this chick you’d like and taken your leisure pills and gone off to Neo City. It was a mundane working class yobbo’s idea of the future. To my amazement people now think it’s quite good.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RNSwIVZSX_g

It rocks.

We’d done a lot of road work and we were young lads. The drummer was only 17 or 18. I think I was 21. We rehearsed and rehearsed it as we thought ‘Crikey. We’re off into the studio. We better practice.’ When we had the opportunity to record in a proper studio in London we thought we better not cock this up. It was early January and we didn’t have any gigs. So we went into the hut where we’d rehearse and played the 6 songs we were gonna do all the way through every night for two weeks.

So when we went into the studio and we were points perfect. Six tracks in one day, we put the overdubs on and everything. We kind of got signed on the spot and of course nothing happened. In fact the tracks lay in the vaults for ages and what you hear is what has been rescued. The engineer said ‘Where do you come from why aren’t you known?’ We said, ‘We’re from Essex’ [laughs]

And now ‘Neo City’ is on the Velvet Tinmine compilation and I think the rest are on vinyl.

Yes, an Italian label brought them out. Not everyone in the band thought we were on the right track, not even me. Remember it was 1975 and glam rock was pretty much dead. I was starting listening to a lot of French stuff and some of the other guys got interested in jazz. We were one of the last human jukeboxes. Bands don’t do that nowadays. In those days the four of you got together, learned the charts, played where you could and did covers. It meant you did lots of different styles of music you didn’t just become an indie band. Good training.

So you later started doing music yourself that is now known as the DIY approach with The Cleaners from Venus.

I didn’t know the mechanisms of the music industry. I’d now made a record and knew how to write songs. It had seemed that every approach I’d had with the music industry ended in disaster. I thought that I couldn’t wait for people to phone up and tell me things were going to happen. So I decided to run my own little music industry and just put things out myself. And how do you get it? Well you phone up or come to the door and we mail it to you. They said ‘How many do you expect to sell?’ I thought if we’d sell 200 that would be quite successful. You certainly regard that a success if you were making teapots. You wouldn’t have to sell 50,000 to be a big hit.

We made cassettes and portastudios had just been invented so it was possible to do it. We got to the point where record companies actually got in touch with us to sell this stuff. We said ‘Sorry, we don’t deal with record companies.’ At one point Lol, from the Cleaners, who was a real anarchist said ‘Should we be taking money for this stuff?’ I said ‘What? We give it away?’ So we came up with a compromise, music for groceries! That would be a direct swap, music for food. But we realised that if it was over a long distance there could be perishables involved, all the implications of someone posting a cauliflower. So we couldn’t have that!

So we took in bits of money and that’s how The Cleaners from Venus ran for a while.

Your work in The Cleaners from Venus is really popular now and ‘Only A Shadow’ was covered by MGMT.

I didn’t realise until someone said. I said to my daughter and her friend who are teenagers ‘Have you ever heard of a band called MGMT?’. They said ‘Yeah! They’re really hip.’ I said ‘Oh, right. Is it good if they cover one of my songs?’. They were like ‘No way!’ So we went on YouTube and looked it up. Did they look at me with different eyes? No, they still thought I was a stupid git, who hit lucky!

MGMT did it exactly the same as we did it. I’ve emailed Andrew VanWyngarden and got a friendly email back. When I did that track I thought it was really good and liked it. I played it to people at the time, around 1983, and they thought ‘Yeah, it’s alright. Not among your best.’ I went ‘Oh, right.’

Listening to both versions highlights that in a different environment, with better luck, you could have been massive.

Yeah, but it’s perfectly as useless as being ahead of your time as being behind your time. I’ve been both. You’re talking to a guy who joined a prog rock band at the beginning of punk! [laughs] Whatever it was I’m the Alfred E Neumann of pop. Whatever it is I’m going to get it wrong. Except I’ll think it’s funny. A lot of people in pop music take themselves too seriously.

Is it right to say that your ‘Under Wartime Conditions’ album was influenced by that particular period.’

Yes it was because (A) I was very poor, (B) there was a miners strike going on. That whole period in the ‘80s politicised me and I’m not a political sort of man, or wasn’t. So from the mid to late ‘80s I became quite political. ‘Summer in a Small Town’ was about that. I was watching not just an irresponsible government doing things but I was watching the very threads of the social tapestry of the country, that I had known, loved and grown up in being interfered with. And that interference, the legacy of that has filtered down through to what we have now.

We opened the podcast with ‘Illya Kuryakin Looked At Me’ that you released a few years later.

That was actually a poem before it was a song. That was quite unusual as I wasn’t writing poems then. It was a stream of consciousness. It was a shopping list of everything I liked in the ‘60s. It took me to the early ‘80s to realise that the ‘60s had been quite good. It was when Mrs Thatcher started stomping on steelworks and miners. Erasing communities and starting wars. I began revisiting my past and eventually the song came out of the poem.

Looking back at The Cleaners From Venus, especially the compilations, it’s just track after track of hit singles that never were. ‘Julie Profumo’, ‘A Mercury Girl’, ‘Girl On A Swing’, ‘Mad March Hare’.

I sort of liked them at the time you know. I wrote them and thought ‘These things are quite good. Surely the world won’t be content to see me starve when I’m producing stuff of this quality.’ But they were only too happy to see me starve by never giving me any money. I thought it was a grand comedy. In my lighter moments I knew they were good. I had darker moments I thought ‘I’m not selling them because they are rubbish.’

But I wasn’t selling them because the whole music business is dominated by a place called London.

London is a place where people talk like this [adopts public school business voice] ‘Good man. I’ve got a window for you Wednesday’ and takes too much of the devils’ dandruff and all that bollocks. So I didn’t like London and I didn’t like business and I decided ‘What if I conduct an entire music career without any fame or any money?’. I came to the conclusion, even now 30 odd years later that it’s much more fun doing without the fame or the money as people who are twats don’t interfere with you. [laughs]

Yeah. There was no one to tip their finger and say ‘Twangy guitars are on their way out Martin.’ Or say ‘I think you should be a little better. You were a bit flat there.’ Imperfection is an ideal striven towards.

I made an album with Andy Partridge and he’s quite a perfectionist. So I went along to see what would happen if I went for perfect. And it was very good and it was alright. But in the end I go back to doing things kind of instantly because I like it. I don’t think anyone one would like me in the music industry for that reason and I certainly wouldn’t like to go to the party. I’d find that repellent. Especially when you see old punks and people like that. You see people turning up in their bow ties turning up at award ceremonies. I think ‘Hang on. Weren’t you a rocker. Surely you wouldn’t go to these things and rub shoulders with these people.’ But they do, don’t they.

So you’re not a perfectionist.

No, it’s the mistakes that make it. It should be my motto ‘Mistakes make the man’!

After this period you went on to become known as one of Britain’s most successful living poets.

I’ve been told I’m England’s most published poet because I’ve had a poem in a national newspaper every week for near a quarter of a century. When I was writing for The Independent it was sometimes three a week and I’ve just got this massive body of work. It doesn’t necessarily mean it’s all good. Some of it is though and I don’t treat poetry as a special thing that only some people in universities have. Academia and Oxbridge in particular have hijacked poetry and treat it as only they understand it. They make it so obscure that nobody reads this stuff anymore because it’s so difficult to understand. It shouldn’t be. The way they combat that is to create these prizes like The Oxford Chair of Poetry. I mean, what the frig is that!

I don’t believe them and I don’t believe in the Arts Council. I don’t trust them, I’d like it all torn down. [laughs] In a kindly way! The best accolade for me is that it’s helped pay my way for 25 years. You just have to write what people want and most poets do not.

That’s what you’ve got in common with John Cooper Clarke.

John’s a friend of mine and is a great poet. He wanted to be a comedian and became a poet because he wasn’t getting work as a comedian, I think. I wanted to be a musician and became a poet at a point I couldn’t be a musician. I could probably do John as I know his material so well.

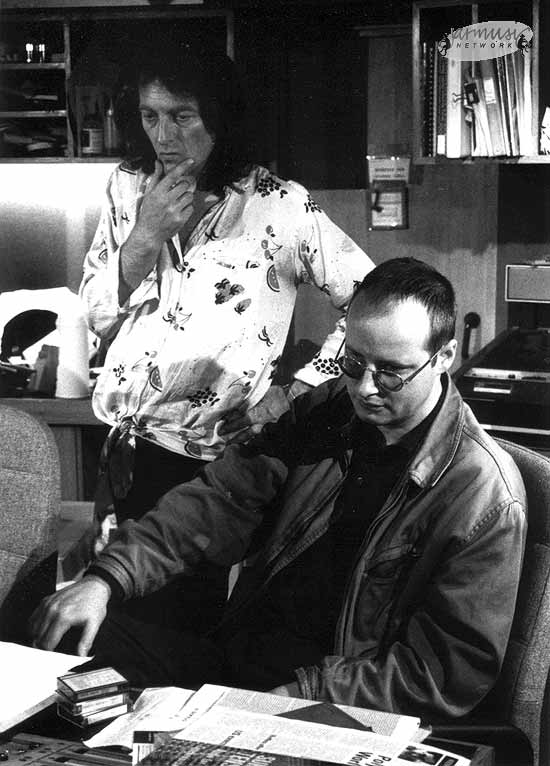

John Cooper Clarke (left) and Martin Newell (right) (photo from http://blog.fixemag.org/post/28420514019/myu-zik)

He’s done a poem for you that’s very complementary.

He wrote it a long time ago when he first met me. [adopts convincing John Cooper Clarke voice] ‘The man has got two jobs to do. He’ll satisfy your horticulture needs. Then he’s got a gig in Leeds. Who’s that? Martin Newell.’ [laughs] It’s like an Alan Whicker convention when we get together. Most of the time we are telling each other jokes and he’s always got more than me. He went head to head with my younger brother once and he lasted an hour and 15.

However in the early ‘90s things started hotting up on the music front again with probably your best known album ‘The Greatest Living Englishmen’. Which Andy Partridge of XTC produced who I’ve always loved. You touched on this briefly earlier, what was it like working with Andy?

Andy had just finished working with the young Blur at the time on what might have been ‘Modern Life Is Rubbish’. I think Stephen Street ended up producing them. Somebody wanted to put me and Andy together because they thought we’d work together. I think they thought I was a bigger XTC fan than I was. I liked them but didn’t know that much about them. Lol and Giles from The Cleaners from Venus were huge XTC fans but I tended to like their singles.

So I met Andy in November ‘92 and he liked my poetry. He’d bought one or two of my poetry books but didn’t know I did music. After he became aware I could write songs he said ‘How come I haven’t heard of you?’. So I had to explain how I hated the music industry and so on. But we ended up working together and we got on like a house on fire. We were like twins who had been separated at birth. Same sense of humour. I think he has a rather different attitude in the studio. He’s not a slap it down and leave it merchant like I am. So I said ‘One of us is going to be the producer and since it’s you I’ll do exactly what you say.’ And that’s exactly what we did. Andy has said he’s somewhere between Santa Claus and Mussolini in the studio.

But someone’s got to be the governor and it just meant I was free to just go and be the artist. I picked a couple of vetoes and just said once ‘You do realise you’re making a Martin Newell album and not an XTC album ok.’ He was very gracious about it. He said ‘Of course.’ A lovely bloke. I didn’t fall out with him but there came a time when we moved on. We were quite close at one point. Very good chap.

Martin Newell (left) and Andy Partridge (right), during the recording of “The Greatest Living Englishman” in 1993 from http://jarmusic.apwb.com/gallery.php?getgallery=main

Martin Newell (left) and Andy Partridge (right), during the recording of “The Greatest Living Englishman” in 1993 from http://jarmusic.apwb.com/gallery.php?getgallery=main

Would you work with him again or was it just that period of your life?

He came along at that period in my life where we had similar things; our different relationships were breaking up. But unlike Sting or Phil Collins we didn’t go into therapy, we just got on with the job. He’s a good West Country lad and I’m East Anglian so it was ‘Well, we’ve got an album to do.’ We were in a lot of pain in our personal lives but never talked about that. We just made filthy jokes and made the record in his shed. It was a pleasure to do, six months with huge laughs and amazing thrills. Two men in a shed. [laughs]

Would I work with him again? That’s really difficult because he did me the favour of what a lot of my listeners and so-called fans would like, of me being produced properly. But I don’t want to be produced properly. I did it twice, I did another album as well with Louis Philippe. However I kind of like things that sound like they were produced in an old radio shack or something.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QEoAuu_ZuFI

But I probably would work with him again, yeah. I wouldn’t push it. I’d like to see him again. I’d like to sit down and have a bloody good yarn with him. He’s certainly a more tidy musician than me and certainly a better and more versatile guitarist. But I don’t think he is as free as me. That happens with a lot of virtuoso musicians. Their cleverness and their ability imprisons them. I am the eternal amateur. I have the idea that I can do anything that I want. I’ve retained a naivety thinking ‘What if we did this’ and if it doesn’t go right make it into something else.

Was ‘The Greatest Living Englishman’ your title?

I think it used to be about Nigel Dempster, the gossip columnist. They called him ‘The Greatest Living Englishman’. There’s various people they give the title to at one point. The song came first as I wanted about someone like Justin de Villeneuve, Terry Stamp or Mick Jagger or Keith Richards even. At some point it’s like their English and the whole world knows them. They’ve come up from nearly nothing, from barrow boy to icon. Someone who could become a rogue but eventually something comes to bring them down. They tumble. Someone like John Bloom of the washing machine empire and was eventually brought down. Some people thought I’d adopted the title for myself and that I was calling myself ‘The Greatest Living Englishman’ which wasn’t the case. But I thought that if it’s got annoyance value I’ll admit to it. [laughs] It’s a good title.

‘Your Winter Garden’ from your album ‘The Spirit Cage’ then seemed to mark a change in approach in your songwriting.

It was the very late ‘90s. I’d been mucking about with jazz chords and my piano playing had got better. I concentrated to see if I could write something I suppose getting in my 40s I thought ‘If I had to write proper songs for grown-up singers like Tony Bennett, how would I go about doing that?’ That was really my first stab at writing something jazz, or torch at least. Then I wrote ‘Grenadine and Blue’ and other stuff. And I haven’t stopped writing since.

So some of that older songwriting like The Great American Songbook is influential?

I think it must have leaked into me. The Americans do very good, goodtime music. Jazz musicians are virtuosos but don’t often write songs they do show tunes. You can put quite a lot into one song. That was my striving to write grown up songs I can’t keep writing about girls and chocolate and how politicians are. But songs are in short supply every time I listen to new music I’m being significantly underwhelmed so I want to write some more coverable songs before I die.

‘The Days of May’ from your new album, ‘Return to Bohemia’ also feels like one of those tracks that will live on.

I hope so. That was one of the ones I wrote after I came back from the dead. But don’t worry I’m not going anywhere, not immediately anyway!

There’s more great songs on your new record like ‘The Royal Bank of Love’. That’s a great concept.

Ah, well. That’s the one I think should be a Eurovision song contest entry. Except the BBC won’t let good songs into the Eurovision; they have what’s called an internal selection process and they’ve done that for a number of years. It was just after my mate Kimberley Rew won. Since then the BBC has been picking the songs and we’ve had nothing but dross, nothing has worked. I think they’re doing it because if we win the Eurovision song contest, we’ll have to hold it and someone will have to cough up. So it’s their job to make sure a shit song gets in every time. So I’m not going to get a song in, and if I don’t I’m going to have to hold my own Eurovision Song Contest on MuleTV.

That’s one of your new projects where you’ve got sketches and vignettes on YouTube.

Yes. Johnny from Soft Bodies records has also got me to do some videos as well. They’re quite good, one is animated ‘Imaginary Seas’ and the other is ‘He’s Going Out with Marilyn’.

That’s a good song.

[laughs] That could probably get airplay if I was a nicer boy.

What’s next?

I’m doing a lot more stuff with Captured Tracks – past, present and future. As well as more things are likely with Soft Bodies as well. I’ve got big plans. I just want to spend the autumn and winter doing a new album. I’ve got the songs.

It’s been a privilege to spend some time with you. You’ve produced some of my favourite records so thank you.

Thank you very much.

For more information on Martin’s projects please go to:

http://www.martinnewell.co.uk/