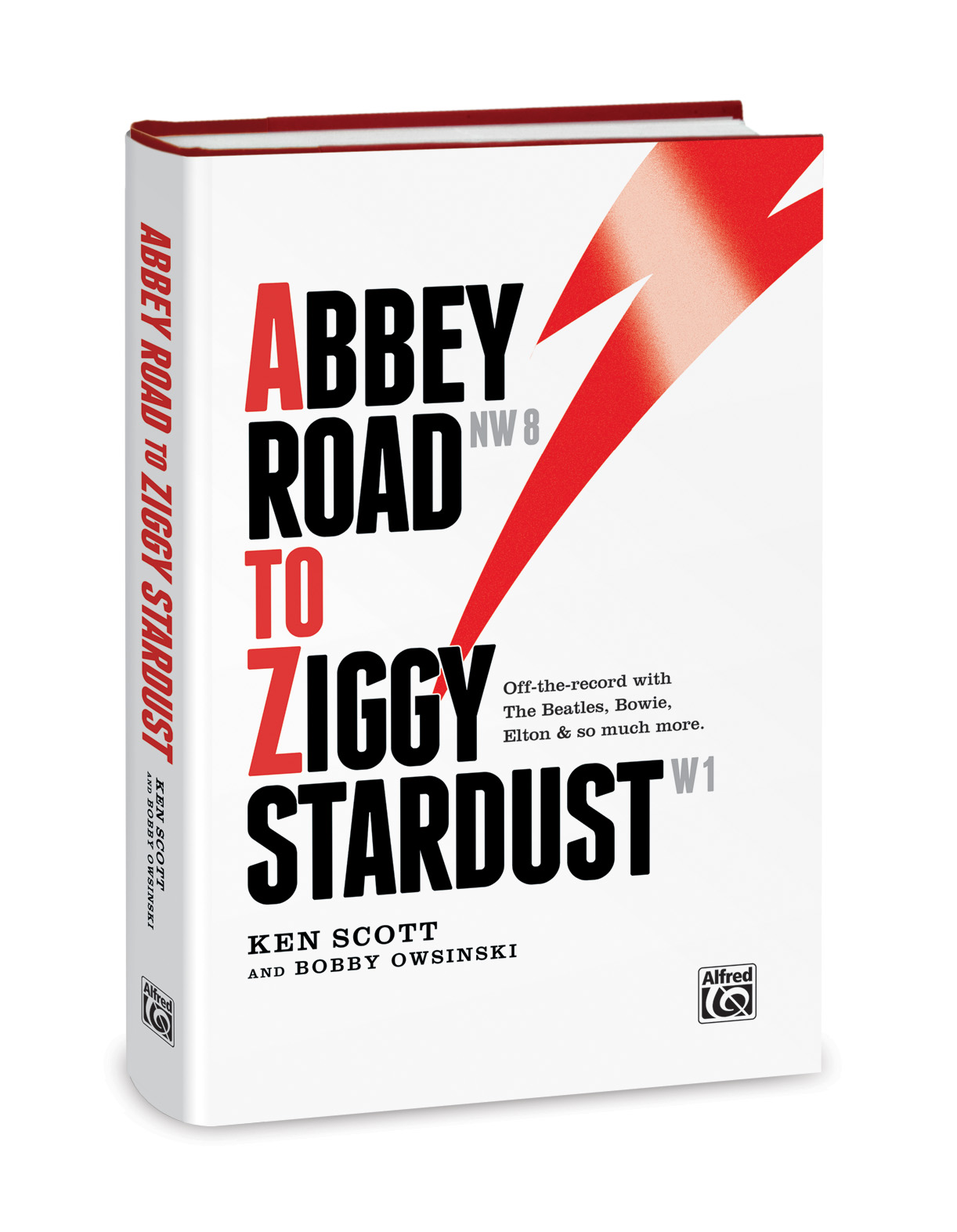

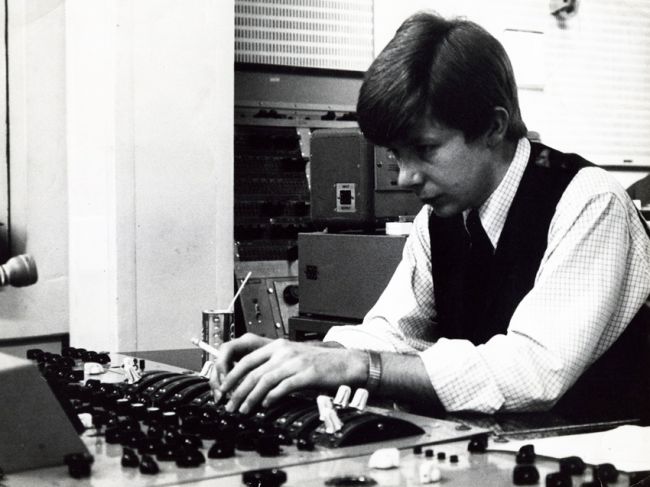

Ken Scott’s work as a recording engineer and producer spans much of the greatest rock music ever recorded. From The Beatles ‘White Album’, David Bowie’s ‘Ziggy Stardust’, George Harrison’s ‘All Things Must Pass’ to Lou Reed’s ‘Transformer’. He has an excellent book recalling his time working with these artists and much more – ‘Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust‘.

Ken speaks to Jason Barnard about his time working with some of the most important artists of the 20th century.

Thank you so much for taking the time to speak to me. I was inspired by going to the session that you did in the centre of Leeds a month or two back. Going from America to Harrogate.

Well, from South East London to Los Angeles to Nashville to North Yorkshire, yeah. I’ve led a varied life.

I really like your book ‘Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust’. It really is an insight into those times and the thing that really struck me about your striving to be absolutely spot on in terms of accuracy.

If possible, yeah, I believe there are certain parts of that period. It was the golden age of English music and a lot of it’s gonna – they’re gonna be talking about it in a hundred/two hundred years, so I always feel that it should be as close as possible to the truth.

Absolutely. I was speaking to Geoff Emerick about six weeks ago and I know that you’ve been very vocal about trying to sort of correct some of the potential inaccuracies that he did in his book.

And, look, yeah. I have great difficulties with a lot of that. Some of the things that I had mentioned got changed between the hard cover and the soft cover, which pleased me but there are (draws a deep breath) – it wasn’t liked by a lot of people that were around at that time, let me just put it that way.

Ken, I understand The Beatles’ I Am The Walrus was the first track you engineered. Is that correct?

Probably the first released track. It was certainly the first orchestral thing I ever did. My very first session was trying a new version of Your Mother Should Know. They’d already recorded a basic track to that song in another studio and Paul wanted to try a different arrangement and I sat behind the board, for the first time in my life, not knowing what the hell I was doing and luckily it wasn’t something that they were going to strive to use later, so my mistakes were not quite as bad as they could have been but, yeah, pretty terrifying times for me but certainly uplifting and absolutely astounding but, no, first orchestral session being with biggest bloody band in the world!

That really comes across from ‘Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust’. A lot of the things that you do for the first time are absolutely sort of pivotal projects. It just seems incredible really.

(Laughing) It’s absolutely bloody ridiculous, quite honestly, but, yeah, for whatever reason it worked first off every time.

And I also read you were there for the mixing of I Am The Walrus and for the famous radio tuning stuff?

Right – King Lear on the Third Programme, which, because we did that live as we mixed and we were mixing to mono, when it came time for the stereo – Geoff Emerick did the stereo mix of it – and so what they had to do they could never emulate what occurred with the radio, at the end there, and so he had to take the mono mix and just make a sort of fake stereo and they cut on “.. sitting in an English garden..” and that’s where it turns to mono. Fake stereo, let me just say that.

Yes. It works really well in terms of the radio aspects of that. You also describe in ‘Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust’ how soon after the Magical Mystery Tour project you worked with the Jeff Beck Group and we’ll be playing Ol’ Man River but you described how the band and Rod Stewart and Jeff Beck were really on form but also I understand Keith Moon was on that particular track and he was as noisy as ever.

He was indeed on that track playing timps. He came in to guest on it and at the end of the session, I think we finished about 11 o’clock at night, he left and he got into his big Rolls Royce which had a rather large PA system on the top of it and, as he was pulling out of the car park, this little old woman was walking her dog and she happened to step in front of the Roller, and he immediately picked up the mike and switched on his PA and started to curse and scream at her, blasting out throughout St John’s Wood, which is a very quiet place at eleven o’clock at night – at least it used to be back then – and EMI Studios, as Abbey Road was then known, got more complaints about that particular outcome or outburst than they had for even having to close Abbey Road down because of all the girl fans outside when The Beatles were recording.

And, soon after that, you worked with The Beatles again on Hey Jude in terms of engineering that track?

Yeah. We were working on the ‘White Album’ and that was something that we did whilst working on the ‘White Album’.

And the interesting thing about that is that the band recorded the song a second time at Trident Studios and you were very vocal about the sound quality of that when it came back to EMI?

Unfortunately, what had happened, we spent two nights, I think it was, trying to record Hey Jude at Abbey Road and some bright spark had given permission for a film crew to come in the second night for a documentary that was being done for the BBC, all about English music. Now the director and producer came by the first night when we were just working on the arrangement of Hey Jude, just to see what the place looked like, what was going on, so that they could sort it out for the shoot the next evening. And, of course, it was the typical film crew thing of, “You’ll never know we’re here; we’ll be quiet as mice; we won’t affect anything; just go on as you normally would.” And, of course, typically that isn’t the way it goes. They stick their camera in your face, you know everything’s being recorded. It’s never the same when there’s video going on, filming going on. So they came in the second night and, because of them being there, it became very sort of difficult to work. There were arguments going on between band members. Everything’s over emphasised because of the cameras being there, so they never actually got a finished take of Hey Jude at Abbey Road. They happened to have three days booked at a new independent studio in London called Trident, which I eventually went to work at, and the reason they went there was Trident was the very first studio in England to have an 8-track recorder. We were still 4-track at Abbey Road and so they wanted to try out the new American craze of recording on 8-track and so they went in there. First night they got a lot of Hey Jude done. Second day they completed the overdubs, orchestra, vocals – all of that – and, the third day they mixed it. Well, I went down the evening of the third day to hear the mix. I sat down in front of the mixing console and it blasted me. It sounded absolutely incredible. I’d never heard anything quite so good. Get back to Abbey Road.

A couple of days later the tape arrives and they’re having these things called playback acetates cut. Playback acetates were the way the artist, the producer, the arranger would get to hear the recording. It was just a small seven inch disk which would last maybe 10/12 plays if you’re lucky. And so someone upstairs was cutting some playback acetates for the band to hear. And I went up and listened to it and it was as if there was a pillow or a very thick curtain in front of the speaker. There was no high end, no top on the recording, so I went back down. George Martin was the first one to come in and he said, “Have you heard it?” and I said, “Yeah. I was down Trident. It sounded amazing.” He said, “No – have you heard it here?” I, sort of, hummed and hawed a bit and I had to be honest and said, “Yes I have and it sounds awful.” And just about that point John arrives and I knew George so well that I know he didn’t say this but it’s just the way it’s firmly ingrained in my brain. He told John that Ken thinks it sounds like shit. John immediately sort of looks at me with daggers and slowly one by one the other members of the band come in and they go downstairs and I see them looking up every now and again and I know they’re talking about me, they’re talking about my comment about Hey Jude and I’m petrified. I think that’s gonna be it. I’m gonna be out on my ear. Finally they all come stomping up the stairs and George says to me, “OK. Let’s hear the tape.” So I send the second engineer up, he brings the tape down, puts it on, and luckily they agree with me, it did sound like shit, and we spent the next five or six hours, I think it was, eq-ing it until it sounded the way you now hear it because it’s never been mixed again. Or it may have been actually recently by Giles (Martin), I’m not sure how much he did on that one for the new CD…

Number ones.

Yeah. But, other than that, it’s exactly the same as we eq-ed it.

Ken, you also mentioned about working on the ‘White Album’ in terms of engineering it and when I saw you at your recent book event you had a great story about the recording of Glass Onion and how sometimes how mistakes can make the track.

Well, yeah, it makes it human. We’re all human and we react in a human way to things and when things are too perfect it just, it doesn’t rub as quite the right way so I’m a firm believer that mistakes are good and The Beatles were very good within that situation. They would quite often listen to a mistake and then decide whether “now we’ve got to fix it” or “maybe it works – let’s keep it”. The Glass Onion situation was one of those. We had recorded a lot of snares. It opens up with Ringo going blap, blap on snare. That happens five times I think it is. We overdubbed a whole bunch of other snares doing the blap blap to make it bigger and then mixed those all down to one track. As we were doing overdubs and overdubs we came to what we thought was the last overdub of George Martin’s assistant and Paul playing recorders and we had to put them on the track with all of the snares. And we’re doing what was called a punch-in where we start recording after the last blap blap, so I have to play the last blap blap, then hit record and then they start playing. Well, after quite a few attempts of it being played I wasn’t thinking quite properly and I went straight into record as opposed to play / blap blap / record, and erased the last bunch of snares. And so the last time you hear it, it’s just a solo snare – just Ringo. And, once again, another one of those examples where I thought I’m out on my ear but John was there and he said, “Take it back – let me hear it once more.” I played it for him and he said, “No one would ever think of having the smallest part of the song come immediately after the biggest. I like it. We’ll keep it.” So, next time you hear it you’ll notice that the last one is very different and it was just because of my cock up.

Fantastic. You left EMI Studios I think pretty soon after that period, I think because of the top brass there, and you went over to Trident but you carried on working with at least three of The Beatles?

Yes. I did some work with John. I mixed Give Peace A Chance there. That was one of the first things I did at Trident. Then I recorded Cold Turkey, which was eventually mixed by Phil McDonald over at Abbey Road. I did work with George on All Things Must Pass and, with him producing, did It Don’t Come Easy with Ringo.

And we’re playing Cold Turkey. Was Eric Clapton on that one?

He was indeed.

And that was John’s quite primal therapy, aggressive period?

That’s my understanding. Yeah. It certainly seemed like that in the studio.

Was it quite tense?

Not, not tense, but just, well, you can tell by the ending of the record that he wanted to put something across and it was as dirty as it could possibly be, sound wise, and just vocally intense, yes.

And in this period you were working with Gus Dudgeon with David Bowie?

I didn’t, actually.

Oh. OK.

The one thing that Gus produced with David was Space Oddity which I didn’t do that particular track. That was engineered by a gentleman called Barry Sheffield. I worked with Tony (Visconti) on the ‘Space Oddity’ or ‘David Bowie’ or ‘Man Of Words/Man Of Music’ album – whatever you want to call it cos it’s been out in three different names. So, yeah, I worked with Tony on the rest of it, not the single.

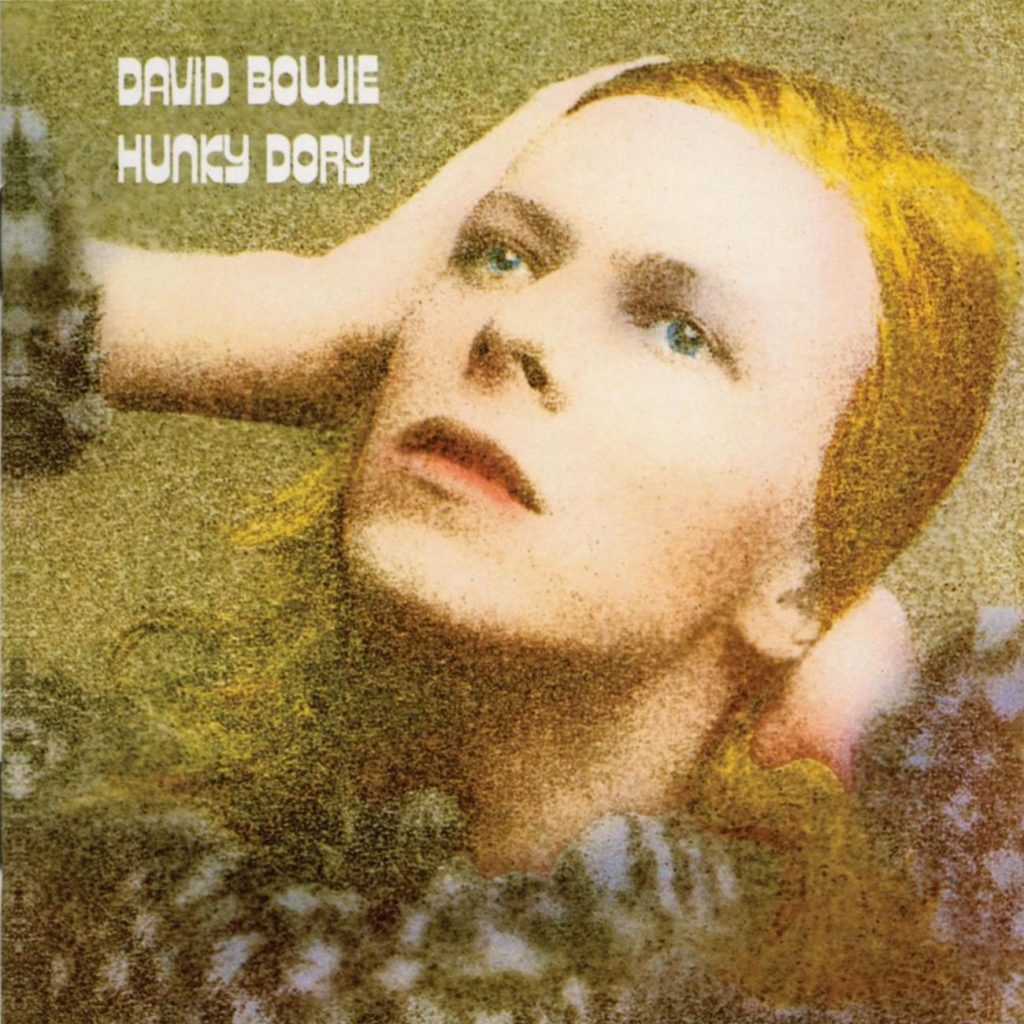

But we were talking about the series of firsts that you had and your first production, big production, was David Bowie and Hunky Dory.

Yep, that’s what happened. I’d got fed up with engineering and David, I was working with David. David was producing a friend of his and, in one of the tea breaks, I happened to mention to David that I was fed up with just engineering, that I wanted to move into production. And he said, “Well, I’ve just signed a new management deal and I was going to produce it myself. I don’t know if I’m capable of doing that. Would you co-produce it with me?” So I did and that’s what finished up being Hunky Dory.

And, at your book event, you vividly went through the range of tracks that made Life On Mars. I mean the way that that track is layered up to become something, you know, beyond the sum of its parts is quite incredible. It’s such a fantastic track.

It is. But bottom line, with all of David’s stuff, it comes down to his vocal performance, as far as I’m concerned on everything, which… I co-produced four albums with him and ninety five percent of the vocals were first take, beginning to end, no auto tune, no cut and paste, no moving around. What you hear on those records is what he did that one time. He was absolutely astounding. Probably the best vocalist I’ve ever worked with.

And was it Rock and Roll Suicide that you played at the book event that was quite incredible vocals?

No. Five Years. He was bawling his eyes out at the end there. When we mix a track, we mix to get the whole overall thing across in a certain way and you don’t always get the nuances of some of the performances from the mix. We try and get those across but, because there’s other things going on, you don’t catch it quite as well, so I found that playing, as I do, starting off with the actual track, fading out the track so you just hear David’s vocal with acoustic guitar at the end there, people are so moved by that vocal performance – what he is giving of himself at the end of that. It’s astounding. You can’t hear it with everything going on but, soloing it like that, I’ve had many people in the audience crying, listening to it, because it’s incredible. But that was David.

And, you mention about… you worked with David before, in terms of engineering, but when you heard the Hunky Dory material you really noticed a significant shift?

Oh yes. I engineered two albums, the Space Oddity album and Man Who Sold The World and I thought David was a really nice guy. Obviously he had a certain amount of talent but, from those two projects, I didn’t think he would ever be anything, really. Not that big. It was when he and Angie, his wife, came over to my house and we were going through demos that suddenly it struck me that, here I go again, my first ever production is gonna be something that people might hear, because he could become a superstar.

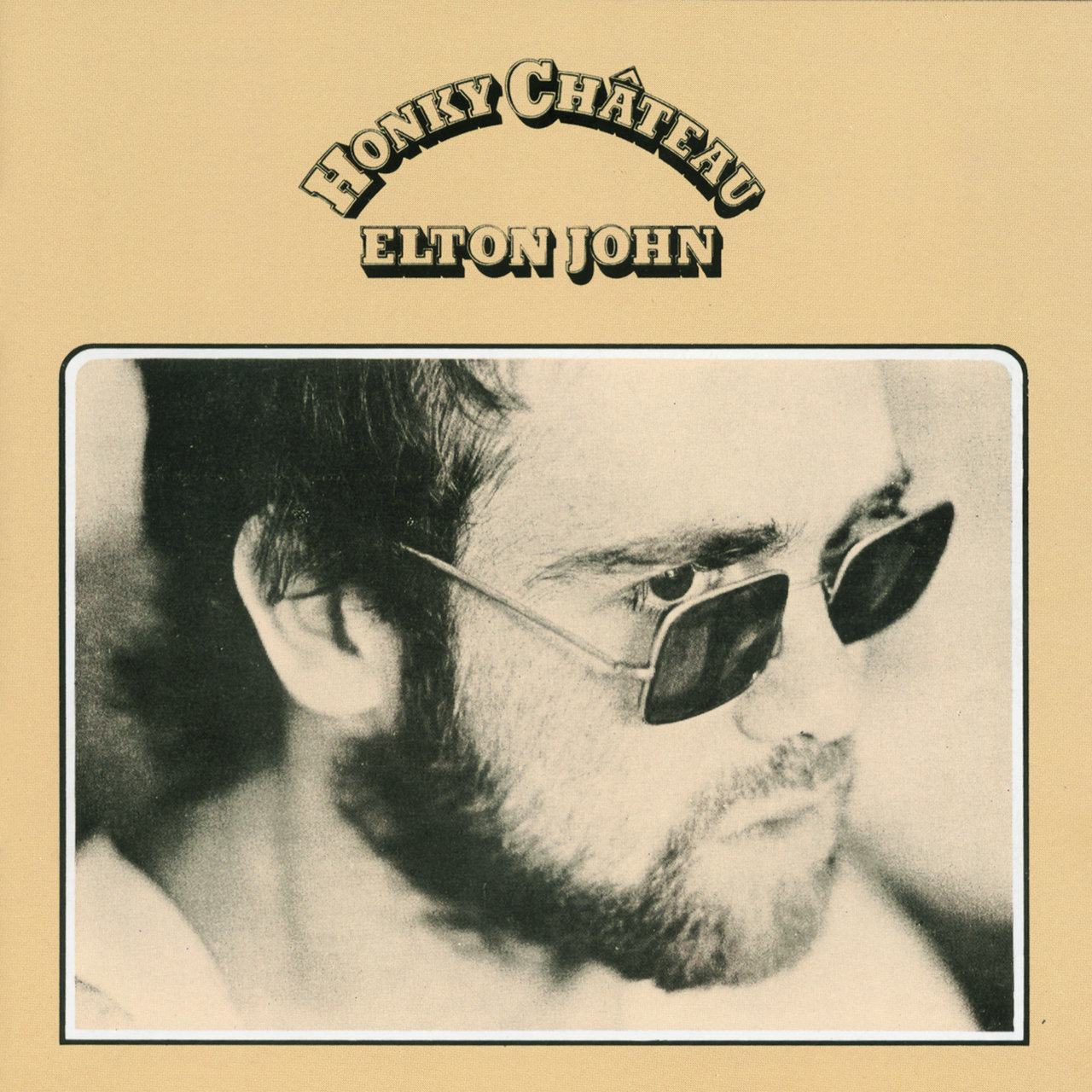

I mean, it’s incredible the range of, you know, definitive artists that you worked with in this period. It does seem such an incredible time in music history really and you worked with Elton John. So you went down to France for the Honky Chateau album?

Yeah, for Honky Chateau and Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player.

And you have a story about the writing – seeing some of the writing process where Bernie would hand Elton some lyrics and then ten minutes later there came Rocket Man?

Absolutely, it was… The chateau, we all lived together and I got there for pre-production and the band was kind of set up in the room where we ate, just to work out songs as they came about. They were all written over in France specifically for the album. Bernie would go up to his room early at night, around about eight o’clock, and he’d come down the next morning, when we were having breakfast, with a sheet of papers – a stack of papers – for Elton to look at and, whilst Elton was eating breakfast, he’d go through, “Yeah, I like that one. Nah, I don’t. No. No. Oh yeah, that’s a good one.” and he’d put it to one side. Then, once he’d finished breakfast, he’d go over to the piano and go through a couple of them and, on this one particular occasion, he stuck up one set of lyrics on the front of the piano and, in ten minutes, had Rocket Man completed. The band just immediately started to work on it and then we went and recorded it.

It just seems so easy doesn’t it?

Oh I know. If only.

Exactly.

One of the great things for me about that time was that the recording contracts were such that the artist had to come up with an album every six months. Now, to keep that kind of pressure up, only the top artists are gonna be able to keep it going – only the most talented people. And they’re the ones that we still listen to today and I fear that this whole thing of the way it is these days of no-one coming out with a new album, somewhere between three and five years after a successful album, it’s watering everything down. They’re trying to second guess themselves too much. It just becomes robotic. It’s lacking a lot of the feel, the soul, imagination, that was around at that great time in English music.

Yeah, and it’s interesting you mention about the sort of time periods between the recording and release of different albums and I think I recall reading that the period between David recording Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust was very brief.

Yeah. It was something like three or four weeks, yeah. His management company wanted a second album in the can for shopping a deal with RCA and so we just went straight in and did it. It was all fine except RCA then decided they didn’t hear a single on Ziggy so we went back in and did Starman and that was put in place of a cover of Chuck Berry’s rock and roll… I can’t remember…

Was it Round And Round?

Yeah, Round And Round.

Fantastic and there’s a quote in the book that struck me was that David said you were his George Martin? I assume that George kind of set the template?

When I was working with George, I didn’t specifically see what he was doing. There were many occasions I thought, “He’s the fifth Beatle, he’s doing nothing.” And I didn’t get it and then when David amazingly said that I was his George Martin, I hit the roof. I actually got mad because, “I did more than George ever did!” And it was only taking it from there and looking back on how I work that I realized how much I had learnt from George. It was with George and now, with me, it’s very much the talent is in the studio for one reason and that’s to create and you, as a producer, have to allow the talent the room to create, always knowing that you can tell them it was better five minutes ago, let’s go back to that. I learnt all of that. Somehow I just soaked it in from George and didn’t realize it at the time. But, that’s what it should be. Everything, in my estimation, everything should come from the studio, the recording room. The sound should come from there. The performance should come from there and, when that happens, we in the control room, we don’t have to do much. We just add the icing on the cake and then we can put our feet up on the desk and just have great music wafting over us.

Yeah and you described Moonage Daydream from Ziggy as one of your highlights as well?

Well, that’s a really good track but one of the things with that was David always used to like to take things from different sources and put them all together and make them his. And the solo on that, which is a baritone sax and recorders, on our version, he loved the sound on the b-side of Alley Oop, a 1960 American hit (by the Hollywood Argyles). On the b-side was something like Sho’ Know A Lot About Love, I think it’s called, and there’s a line that’s played most of the way through it which is a baritone and a flute. And, as I say, David loved that sound so we recreated it in our own way on Moonage Daydream for the solo.

Fantastic. And you continued to work with Mick Ronson and David on the Lou Reed album Transformer? Although I’m not sure you got full credit on that record?

Oh whatever. (Ken chuckles) There was no difference in the working relationship on that album than any of the four David Bowie albums that I got credited on so it’s whatever, whatever…

And again you describe Walk On The Wild Side as really special and Herbie Flowers’ bass line as well.

Absolutely. I have to admit that I’m not a big fan of the album as such but that particular track is absolutely brilliant – from the song, from all the musicians. Herbie’s bass playing on that, the whole idea of the upright bass doubled with, well not doubled, but with the electric bass on top of it, and then Ronno’s string arrangement is phenomenal. And then, Ronnie Ross at the end playing the sax and the weird vocal from Lou on top of it, it just works so well. I love it.

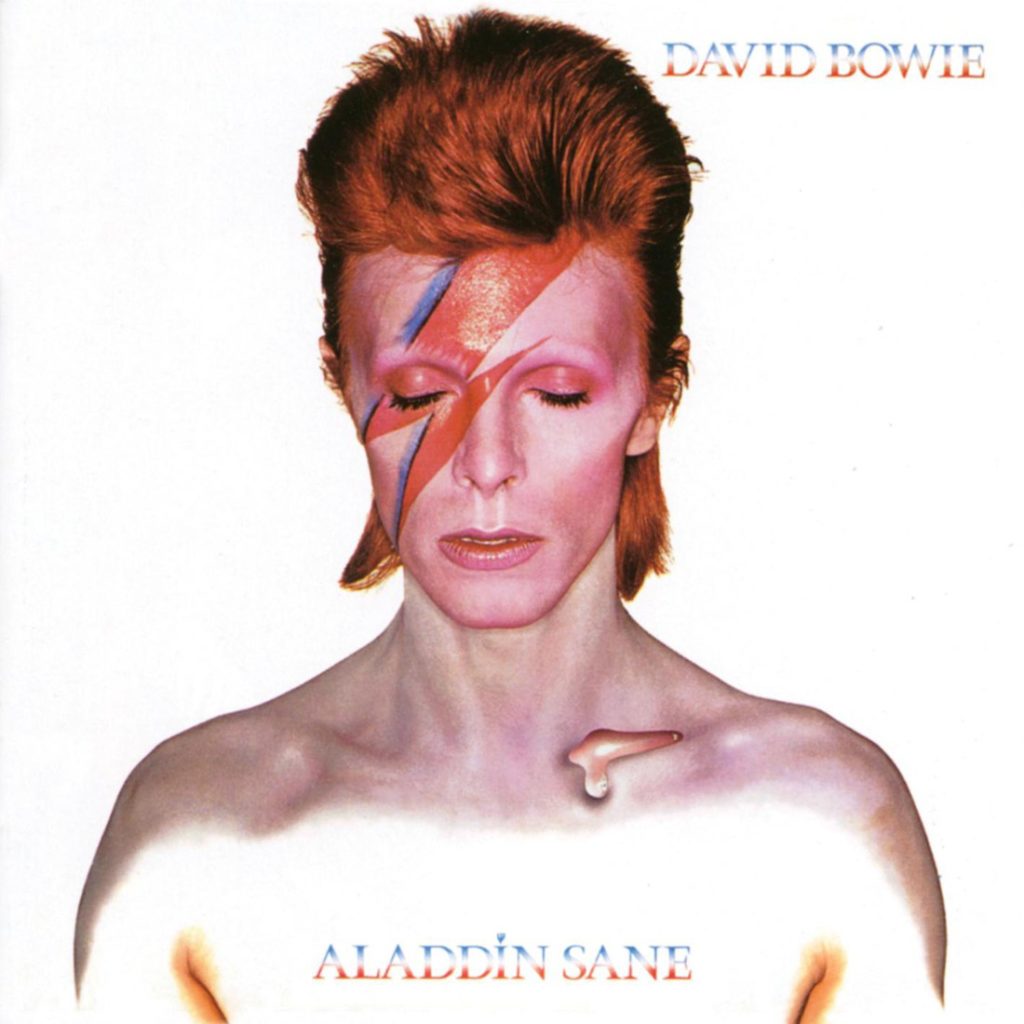

A little bit later you continued to work with Dave again on the Aladdin Sane. Cracked Actor, I think, is one of your highlights. I understand that there were some cracks in the band starting to show in that period.

Not really. There was one point where Woody couldn’t play a part the way David wanted it so that got a little tense but, other than that it was generally OK.

Right.

But it became fairly obvious very soon after that that something was going on because that’s when the band was fired after the Hammersmith Odeon gig and the only member of the band that knew what was going on was Ronno. It was a complete shock to Trevor and Woody.

I guess David was someone who just follows his muse from an artistic level and works with, or finds the right people at the right time, to work on the projects that he wants to make?

Absolutely, and he obviously was already thinking… shortly after that. I don’t know if he was thinking of it during the Aladdin Sane sessions but, shortly after that, he started to get into the whole American soul type thing. I did something. Let’s see. Immediately after Aladdin Sane we did PinUps. That was really strange. Certainly not my favourite album I did with him. A couple of tracks I like but that was weird. He was changing at that point. Then after that I did another recording with him at Trident. It was a song which was called Dodo/1984 or 1984/Dodo which finished up being two songs on Diamond Dogs. When we were mixing that – David only ever came to two mixes on the entire four albums that I did with him. This particular track was the second one that he came to and the entire time he kept on referring to, I think it was a Barry White album, but he kept on saying, “I want it to sound more like that. I want it to sound more like that.” So he was obviously at that point already thinking ahead to that period in his stylings, even though he didn’t quite get there with Diamond Dogs. It took that album before he got there but he was thinking ahead and he had this incredible ability for finding musicians like, if you think of the guitarists he’s gone through, the keyboard players he’s gone through – absolutely remarkable way of picking. He is kind of, in my mind, is almost like a John Mayall of the, uh, more of the pop idiom. Mayall had incredible musicians going through his band all the time from Clapton, Mick Fleetwood – a whole bunch of them – and David was very much the same way from a guitar standpoint, from a keyboard standpoint. He was brilliant at that.

And you kind of moved into a different genre in terms of your production work into sort of the jazz/rock space as well. It comes across in the book that you kind of really enjoyed that new thing and you worked with Mahavishnu Orchestra and I’m playing Open Country Joy from the Birds Of Fire album?

Cool. It was a very strange thing coming to me for that. It was basically a jazz band, which I’d never worked with before and, for some reason, and no one could quite remember exactly why, for some reason they decided to come to me to do the second album which was Birds Of Fire and that started a whole stream of recordings for me, which was great because I get bored very easily. I can’t – I hate making the same record time and time again. I couldn’t do it. So that gave me a whole different area that I could go to from time to time, just to stop my boredom, so it was incredible.

The band really appreciated some of your attention to detail like, on the drums, for example?

I guess because Billy Cobham, the drummer of the band then asked me to work with him on his first solo album which was Spectrum and we went on to do another three albums together after that. Then, because of Spectrum, a bass player called Stanley Clarke asked me to work on three albums with him and it just carried on like that. It was great.

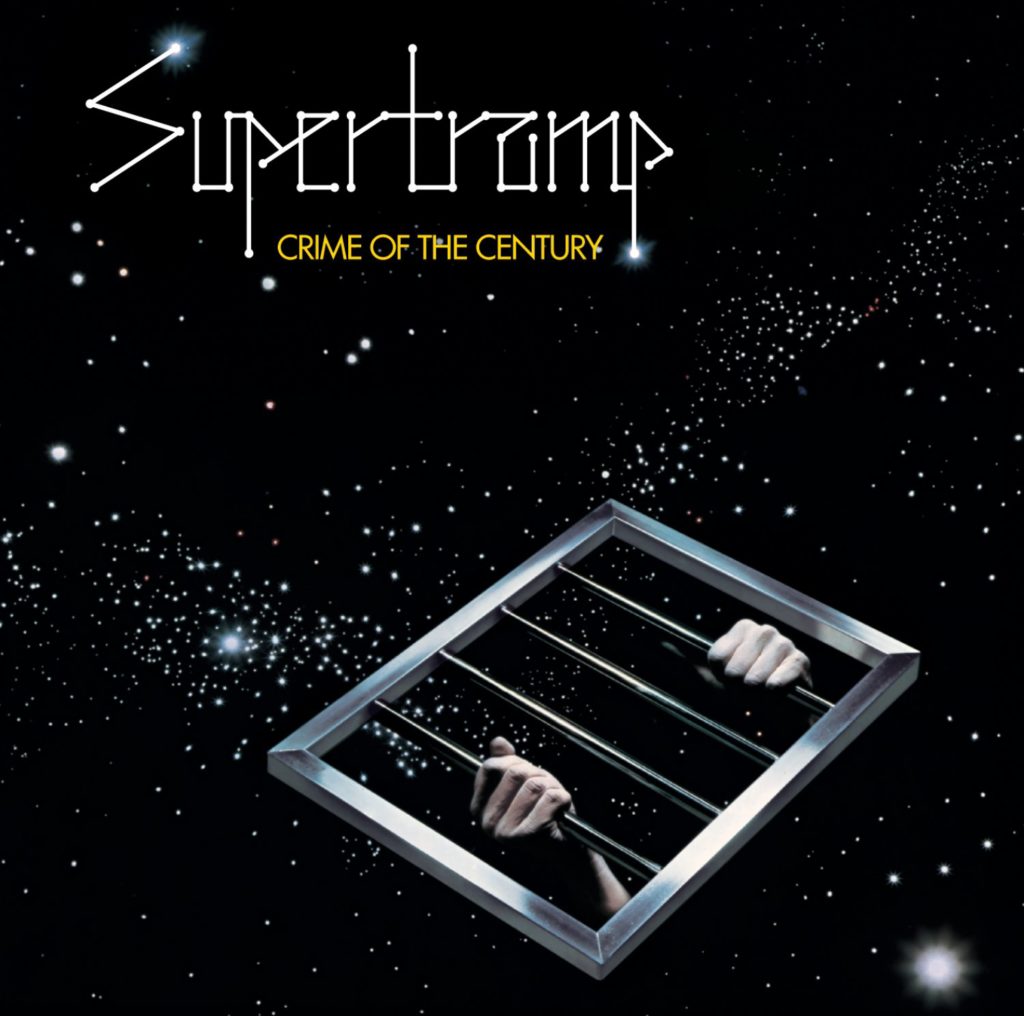

Fantastic. And you later also worked with Supertramp on their very well regarded Crime Of The Century album. I’ve chosen Dreamer but the other thing that struck me about your time working with Supertramp, was just the length of time it took to record an album. I think six months in Crime Of The Century’s case?

On and off, yeah. It stretched out about that amount of time, I think, which was very unusual. We were still in the two albums a year point then, but there was something and I have no idea what it is. I have this inner voice from time to time that tells me to do things that I don’t understand why but I’ve learned to go with and it kind of spoke to me at that time with regard to ’tramp that, “Gotta make it very special.” It has to be bigger and better than anything you…. I can’t say anything you’ve done before, but it just has to be big and really, really good and so, just with the drum sound. Whereas normally we would get all of the sounds and we’d start cutting basic tracks within the first day, so we’d normally have two tracks at the end of the first day’s session, it took a day and a half just to get the drum sound on this, let alone anything else. And so I was dragging it out and we got very worried because about a week and a half in, which is when we should have been getting close to finishing, we had the basic tracks with some rough vocals on, but we were way, way, way behind and we got a phone call that Jerry Moss, the ‘M’ of A&M, wanted to come in and hear what we were doing and we tried to talk them out of it. “No, no he can’t, he can’t.” We were terrified we’d get thrown out of the studio because we hadn’t done enough. Finally we couldn’t dissuade him and he came down and he listened and he, very nicely, just at the end of it, turned round, “Thank you. Thank you.” and left. We thought – that’s it. Tomorrow we get the phone call, it’s all cancelled, they’ve lost their recording contract. It finished up being the complete opposite. We got a phone call the next day saying, “He loved it. Jerry loved it. He can see where you’re going with it and he says just keep going. You have as much time, as much money as you want to finish it the way you’ve started it.” and that’s why it took six months – we took him at his word.

It shows as well cos it is just a gorgeous sounding record.

Well, thank you.

Next, Ken, you then sort of moved over to LA?

Yes. I moved over in 1976.

And you were working with The Tubes and we’re playing Don’t Touch Me There. That’s a really cool track actually. They seem quite a sort of underrated group?

They were. Unfortunately record companies didn’t really know how to deal with them. If you went to see them live, you’d never quite know what to expect. They were almost a comedy troupe but an incredibly musical comedy troupe. Their music was brilliant. One day you might go and see them and it’s just the band that’s playing. The next time you might go and see them and there’d be trapeze artists, twelve dancers, a juggler, a fire eater and people running from the back of the audience as terrorists. It was very bizarre, all of their live performances but, in the studio they were completely professional until someone would walk in, a stranger would walk in, then they suddenly got strange for a bit because they had to keep up their image, and the amazing thing about working with them… Normally, within an album project, you try and keep it so that it’s obvious who the artist is, in some way or another. You keep something that’s similar, whereas with them, number one, there are three different singers and their style of music was so all over the place that we just concentrated on making each track sound as much like the genre that it came from as possible. I didn’t have to keep it so that, “This is The Tubes. Everything has to sound like one band.” And with Don’t Touch Me There it was all out trying to make it as much of a Spector – Phil Spector – type sound as possible. We even got in his string arranger to do the string arrangements for it, to get as close to the original as possible, and that’s Don’t Touch Me There.

A few years later you embarked on management as well and, for me, that really highlighted the role that managers can having in shaping and actually being involved in the creative process.

That’s my belief of what management can and maybe should be. I don’t know if it should be like that but, for me, that was an essential part. I started off working with the band who eventually became known as ‘Missing Persons’, started off just doing demos with them. We tried to shop a deal, couldn’t get one, so we finished up putting out a record ourselves which did very well and, because of how well that was doing, management was needed. We shopped around all of the top managers at that point in LA and, either they didn’t get it, they weren’t interested in the band. There was one manager that was really interested, but he just wanted the singer, he didn’t want anyone behind her. She was the least talented of the lot basically. All of the musicians were ex-Frank Zappa people and Dale, the lead singer, she’d been on, she’d done a couple of vocals on Frank’s records, more talking than singing. So then, when we couldn’t get a manager, someone had to deal with everything on a day to day basis, so it was time for me to put up or shut up and so I became their manager as well, which lasted until we’d sold 800,000 units on the first album and they thought they’d done it all themselves and fired everyone around them.

Gosh. We’re playing Words which I think was one their bigger hits. It’s a really cool track actually.

Yeah. It’s good. I’ve seen a lot on social media. People who know of Missing Persons and Dale, they feel that there are a lot of talents, singers around, female singers around at this point, that owe a lot to her styling and what we did with Missing Persons. Lady Gaga’s copied some of the makeup things that Dale did, some vocal stylings. Gwen Stefani, she’s also taken – and she was around in LA at the time when we had the success – she was playing clubs at that point with No Doubt and she seems to have taken a lot of stylings from Dale as well.

And our last track today is George Harrison. Obviously you originally worked on All Things Must Pass in 1970, around that period anyhow. But you also worked with George towards the latter end of his life on the thirtieth anniversary edition as well. That must have been quite an experience.

It was absolutely astounding. When I first moved over to LA, I was doing a lot of work at the A&M studios which originally – great place. It used to be Charlie Chaplin’s film lot and it had been bought by A&M and you’d walk into the studio and there, in the concrete steps leading into the studio, was Charlie Chaplin’s really small footprint. And it had a great, great feeling around the lot at that point.

When I was there doing the second Supertramp album ‘Crisis What Crisis’, George would stop by every now and again because he’d set up his own label, Dark Horse, through A&M. So he’d pop in every now and again. Then he wasn’t doing as much with Dark Horse, so I didn’t see him around a lot, then I’d stop working there and working other places, so we drifted apart. Hadn’t seen each other for ages and one day I suddenly got a phone call from him, completely out of the blue, that would I be interested in working with him again? And one of the things… we met up and it was great. It was just like old times and one of the things we finished up working on was the reissue of All Things Must Pass, doing additional tracks, working on additional tracks to put on the CD as bonus material and, yeah, it was amazing. He was an incredible guy. One of the funniest people I’ve ever met. Anyone that says he was always sort of dour and angry and all of that, he wasn’t. There were certain things that would set him off, absolutely, but he was hysterical.

And you specifically chose I Live For You from that marvelous record for the podcast. Why was it you chose that song in particular?

One was because my wife Cheryl absolutely adores that track. I was working with George over at Friar Park, his home in Henley-upon-Thames, and she came to join me for a bit and she came up to the studio and it was the first thing I played for her and she’s loved it ever since. So, on a personal level, there’s that. Then, it’s just, I love the track. It’s so good and the fact that it never made it onto the original album, I could never understand. George didn’t, wasn’t as fond of it as he was of the other tracks. It’s just a great, great song. The Pete Drake pedal steel on it is incredible.

It doesn’t have all that sort of Phil Spector type production on it either which, at times, can be a little bit sort of too full.

Oohhh. Tell me about it. When George and I… It was a very strange situation working on that project. George and I just burst out laughing, looking at each other because, there we were, sitting in his studio listening to exactly the same tape as we’d listened to thirty years before, sitting in the same kind of positions. That was funny enough as it was, because thirty years (ago) no one ever thought we would be talking about it, let alone working on it again in thirty years’ time, but then just hearing all of that reverb, we both… We couldn’t understand what the hell we were listening to back then. It really bothered us and we would have loved to have freshly mixed it, done the kind of ‘Let It Be… Naked’ thing of getting rid of a lot of the Phil Spector, the Phil Spectorish sound that all of the reverb and all of that kind of thing and done it more basic, a more basic mix, but the record company didn’t want that at that time. George, the bastard, went and died so we never got round to doing and I have to admit I hope that it doesn’t get done now because I think it’s something that George should definitely have been a part of and, as he’s not around to do it, then I don’t think it should be done.

Yeah. You talk in the book about where albums are remastered or reissued, it’s important that, where possible, the artist and the engineer or producer is there so it stays true to its original release.

There are two ways of looking at it and one is that you keep as close to the original as possible and the other is you completely revamp it. I got to mix Ziggy Stardust in 5.1 surround sound and I asked the record company, okay, I could do this in two ways. I can modernise it or I can make it the way it was. And they said we’d love it in both, but it’s considered the classic album so you should keep as close to the original as possible, which is what I did. But it can be either way. So often, the people that were originally involved in the project aren’t brought in for remastering of remixing or any of that kind of stuff. It’s passed over to someone who had no concept of what we were going for originally and that was a great thing with David with the surround sound mixes, when he was approached for them to be done he insisted that the original producers worked on them, otherwise they couldn’t be done, which meant that I did Ziggy, Tony did I believe two – I think there was the live Ziggy project and one of the others; I’m not sure which it was. To me that’s the way it should be. We know what we were going for and we should be there to do it but, invariably, that doesn’t happen.

Thank you so much Ken. What a privilege to speak to you. I’ve spoken to a lot of people in the business but the range of music that you’ve worked on is up there with anyone, obviously. You know, you were there for the formative and most creative and, arguably, the peaks of rock and roll music history and that’s something else.

I’ve led a very blessed life, yes. And thank you for your time Jason.

More information on ‘Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust: Off the Record with The Beatles, Bowie, Elton & So Much More’ by Ken Scott and Bobby Owsinski can be found here.

Also available from 2018: Ken Scott talks to Jason Barnard about the recording of The Beatles’ White Album which is set to be re-released on 9 November to celebrate its 50th anniversary

Copyright © Jason Barnard and Ken Scott, 2016. All Rights Reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the author.