Trevor Midgley speaks to Jason Barnard of The Strange Brew Podcast

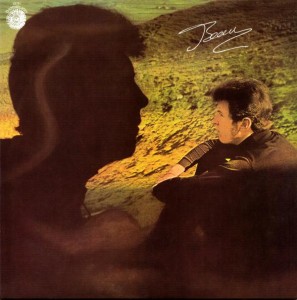

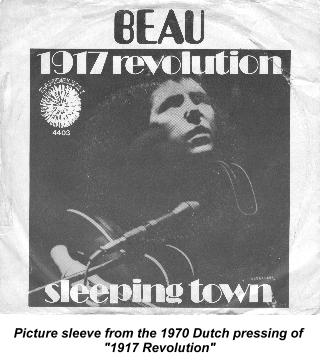

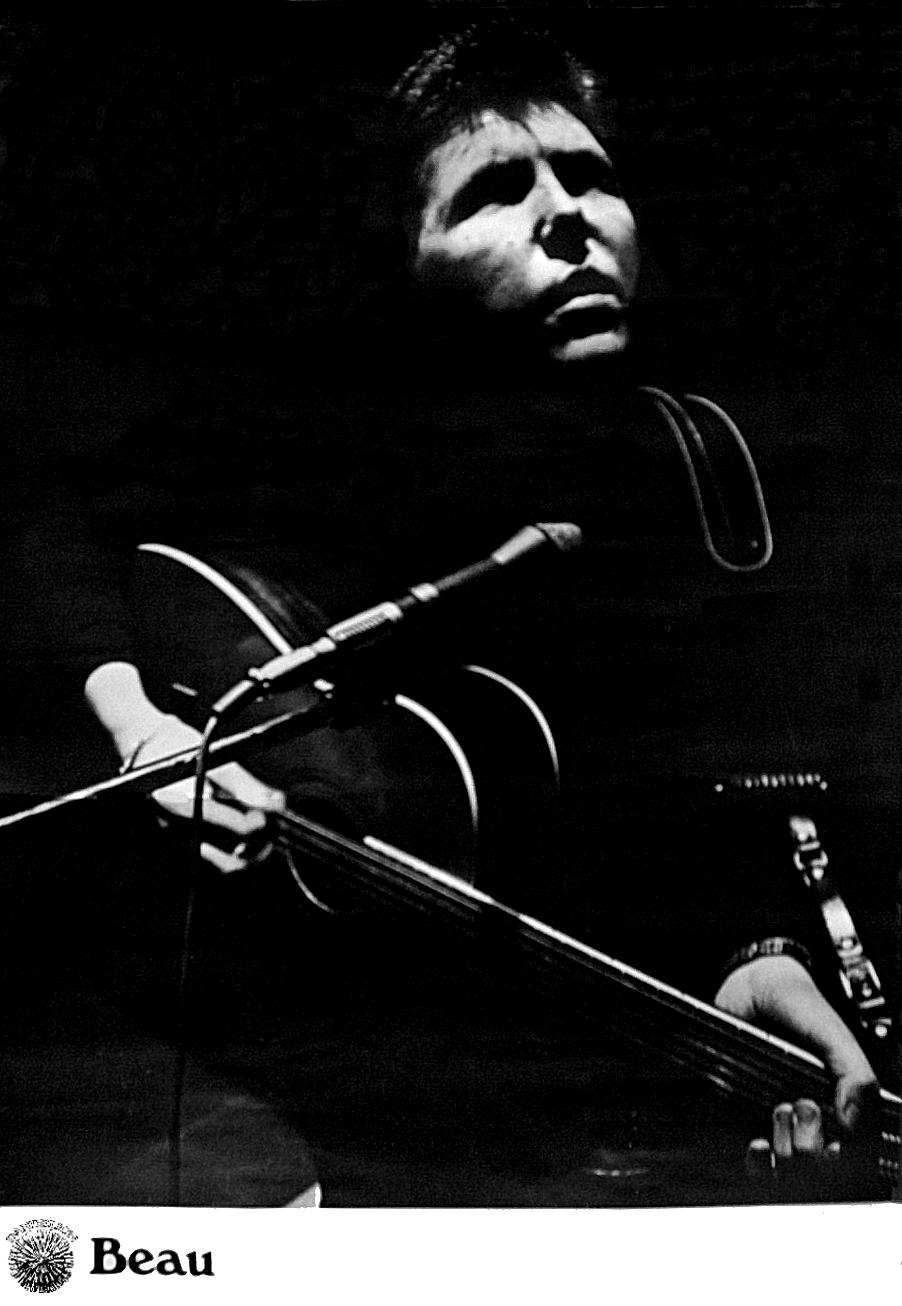

In July 1969, as Beau, Trevor Midgley released the very first single on John Peel’s Dandelion Records, followed by two critically acclaimed albums prior to the label’s demise. His material varies from the striking folk guitar of ‘1917 Revolution’ to heavier tracks such as ‘Silence Returns’ which continue to capture significant worldwide attention. The past few years have seen great interest brought about with the highly praised reissue of his debut album and release of his excellent Edge of the Dark unreleased collection. Trevor provides a fascinating insight into his songwriting, records, career and what it was really like working with John.

Simon Crisp’s Review of Beau’s 1971 album Creation (Galactic Ramble, Foxcote, 2009):

Beau is “a talented singer-songwriter with a superlative 12-string technique… His voice suits the introspective (but never maudlin) material, and his guitar technique is masterful. For example, the simple, almost repetitive, chord sequence on ‘Blind Faith’ brings a depth of emotion that simply shouldn’t be possible… An unexpected bonus is the contribution of labelmates Tractor on two superb tracks – ‘Creation’ and ‘Silence Returns’. The former could almost be Hawkwind, as Beau whispers the lyrics in a eerie and threatening manner against a background of sound effects, while the latter starts with a gentle lament before descending into a frenzied 3-minute guitar thresh that fades out with some ethereal and chilling 12-string. Quite simply superb and well worth investigation.”

Let’s start from the beginning. You’re from Leeds, born in 1946.

Nine months and three days after my father was demobbed.

What was your childhood like and was it Elvis that got you into music?

My mother was bought a piano in 1921 and was supposed to learn to play but never did. This piano was parked permanently at my grandparents’ house and at the age of six I started playing. Or more exactly hammering. I learned to play by ear and I became quite decent. Never did learn to play with music. I did have a piano teacher but the trouble was, if she tried to teach me something specific, I picked it up by ear and I didn’t bother with the music. It’s one of those things which can be either good or bad. The good bit can be your interpretation but you miss out on the technicals. Then we get through to 1956, which was when I first heard Elvis. Up to that point all I’d come across were things like jazz, Frank Sinatra and Lee Lawrence. They meant nothing to me; then suddenly I heard Presley and I thought yes – this is it! In 1957, when he brought out ‘Jailhouse Rock’, that absolutely blew my mind out. I became absolutely obsessed with Elvis and so my whole musical thing developed really from there.

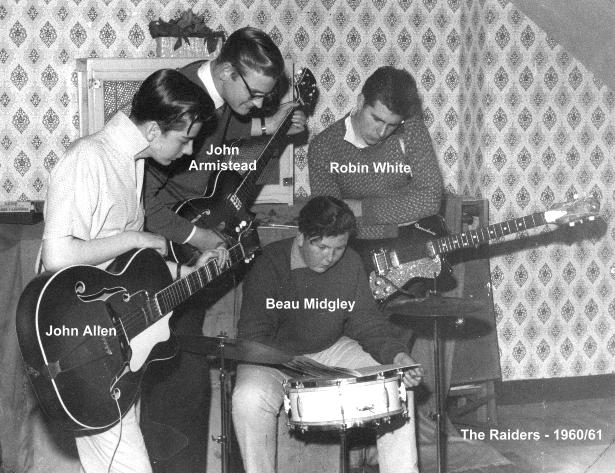

From the British end, by 1959/60 the Shadows were out there with Cliff and we decided to start a band in Leeds. I was at Leeds Grammar School. The band was called The Raiders and we had a guitar player called John Allen from Bramley. We didn’t have a drummer and so it fell to me to play drums. So I played with the band on early Shadows stuff on drums. We played at our first gig at a school hall at St Chads in Leeds. I was there on drums, a mate called Robin White was on lead guitar, John Armistead was on bass and John Allen was on rhythm. The only thing was, we needed a vocalist to do Cliff and the Shads material, and I was the only one who was prepared to sing. The first vocal we ever did was a song called ‘We Say Yeah’ from the film, ‘The Young Ones’. The Raiders carried on for several more gigs when unfortunately Rob White had to temporarily drop out. John Allen took over lead guitar and as I’d been practising rhythm guitar, I took over his slot. A guy called Alan Petch joined us on drums.

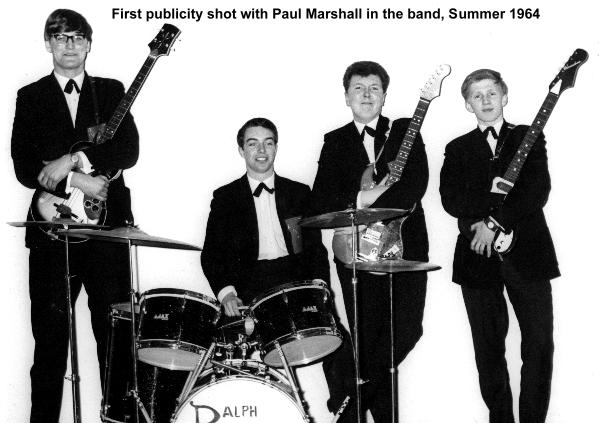

Years later I found out that John Allen had been trying to get me out the band but the others said “He stays, you go!” I never knew why Al had left. Anyway, I took over as lead guitar and vocals. Alan Petch left and Ralph Sims took over the drum seat. When Rob eventually left permanently, we were joined by Paul Marshall on rhythm and sax. The Raiders stayed together with that line-up until eventually Ralph Sims had to leave to go to University. So you can see, rock and roll is my origin, not folk. But then I heard Leadbelly in 1965. He brought me to two things. One was 12-string guitar which I’d never really heard before, and also the politics of song. I’ve always been very political, though never party aligned. After Leadbelly I began listening to Tom Paxton, Phil Ochs, Bob Dylan and dozens of other guys. I realised the power of the song allied to the solo player, and also song writing. I’d started writing some stuff towards the end of The Raiders, but it tended to be straight pop. We did rehearse one or two, but never played them live.

As soon as I got really into the 12-string and contemporary folk scene, it started coming through to me how I could use song to get over my political ideas. From the age 18/19 the writing really did shift. I was prolific. At one point, for a year to 18 months, I was writing two or three a week.

Was it this material that was on your first album or was it that you moved on from it and developed?

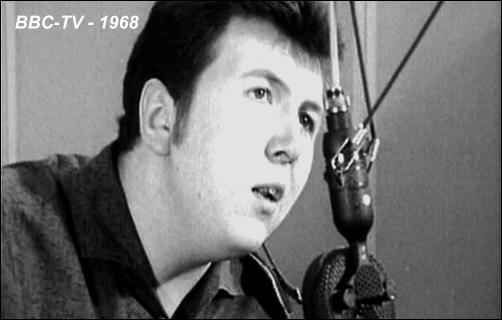

The latter. I probably wrote 25 or 30 songs before I had something I thought was good enough. In ’68 I went down to Polydor in London to do an audition for Elektra Records. I played 22 tracks for Clive Selwood who was the UK manager for Elektra. Elektra handled Paxton and Phil Ochs. Clive said “Yes, I think we could be interested.” But this was at the end of the true solo folk singer boom. They were getting into the Doors, Love and people like that. Anyhow, I laid down all these tracks for them and afterwards Clive asked me for a lift to Slough as I was playing at Reading University. While I was there my 12-string got nicked out of the van!

I had to get another 12-string so I came back to Leeds and I got my Harmony 1270. I got it home and the first thing I played was this arpeggio. That became ‘Welcome’. If you look at it from that perspective, it was welcome to the guitar and the new sound and, as it turned out, it was welcome to the album as that became the first track on my first LP. Had I not got the Harmony, ‘Welcome’ would never have been written, as it really came out of the way the guitar sounded.

It was a great way of introducing a new artist. However, weren’t you knocked back by Elektra but Clive wanted to sign you for the new John Peel label, Dandelion?

Clive took the tapes over to Jac Holzman in New York as Jac had the final say on all things Elektra. They had a some UK artists, like the Incredible String Band. But like I say, they were moving away from solo acoustic folk. Jac said “No, he isn’t what we’re after”. So Clive came back to me and said “I’m with John, I manage John and we’re starting up a new label called Dandelion.” They said they wanted to start with an album, which surprised me as I expected a single because that was the norm. But Clive had heard the 22 tracks I’d put down at Polydor so he knew there was the material. Then everything shifted really quick.

Was the album released before or after the ‘1917 Revolution’ single?

‘1917 Revolution’ was released about 2 weeks before. Bridget St John’s album was released before mine but my single was released before hers. ‘1917 Revolution’ was the first record to be released by Dandelion.

What are your favourite songs from the Beau LP?

‘Revolution’, yeah. ‘Pillar of Economy’, that appealed to me very much. My mother never really liked that song. I was saying to Clive that I liked it. He said “I like that Beau, good track”. But I replied that my mother didn’t like it. He said “Yeah, that’s excellent, if your mother doesn’t like it, that’s good!” ‘The Painted Vase’ was a true story, 95%. The vase was owned by grandma, and it was inherited. The only thing was it didn’t get smashed up in the war.

Another one I particularly like is ‘Morning Sun’. It came out on the album sounding better than I thought it would and I don’t really know why. Something just worked on the day. I used a capo on the 4th fret which I hardly ever used. That gave it an extra dimension. And I like the idea of using a seven syllable word – in-div-id-u-al-it-y.

‘A Nation’s Pride’ is an interesting one. Pretty well the whole album was recorded on the 14th April 1969 down at CBS Studios in London. Then I came home. I used to go out late at night and just drive around by myself. A couple of nights after the sessions, I was driving around and suddenly the song came to me. I pulled over and I worked the whole thing out in my mind, the tune, the chords and the words. The following day I was back in London as Clive had decided that he wanted to try to re-do ‘Revolution’ for a single – the original was thought at that stage to be too long. He wanted to knock out the middle verse, but as it turned out, it didn’t work. After the aborted second version of ‘Revolution’ I said to Clive “I just wrote this song last night”. We thundered away with ‘A Nation’s Pride’ and after the last chord there was a silence and Clive said “Jesus, I like that!” I said “Do you want me to do it again?” he said “No, don’t touch it.” It was the only time it was ever recorded, one take, it wasn’t even supposed to be there. I don’t know why it wrote itself.

The album got good reviews at the time from Record Mirror and Melody Maker.

Yes, but I’ve always had better sales and more feedback from abroad.

You had a number one in Lebanon with 1917 Revolution!

Yeah, that pleased Clive and John. They thought they had a hit on their hands! That was good publicity. They reckon the records got there from Italy or Greece.

How much contact did you have with John Peel? Did he have much influence on your material?

A fair bit of contact at the time because John was always around. He was a lovely guy, he was like he appeared. There was no edge. He was laid back. John hated confrontation with anything or anybody which was why Clive and Shurley dealt with everything business-wise. John turned up, he’d listen and be available to talk. He’d chuck in little bits but he’d never try and influence what you’d be doing. Ever.

Several of the people on Dandelion seemed to think that because we were working with Peel it meant John would push us on Top Gear. There was no way. He couldn’t go pushing his own label. Just the simple caché of being on the label was a mark of quality. The John Peel connection was very important, more important than getting played. He played relatively little of the Dandelion catalogue on his show but several sold quite well. His name had credibility worldwide.

Don’t miss reading the second part of the Trevor Midgley interview by viewing the “Beau – There Once Was A Time– Part 2” feature: