By Nick Warburton

English singer Andy Keiller witnessed the nascent R&B scene in West London before moving to South Africa in March 1964. There he recorded a solo album and single before forming R&B group, The Upsetters with future Influence guitarist Louis McKelvey, another West London émigré, in late 1965. Remarkably, the pair reunited by chance two years later in Montreal and formed Influence – arguably one of the most dynamic bands to emerge from the Canadian rock scene. On the eve of Pacemaker’s long-awaited CD release of Influence’s lone album, he talks to Nick Warburton.

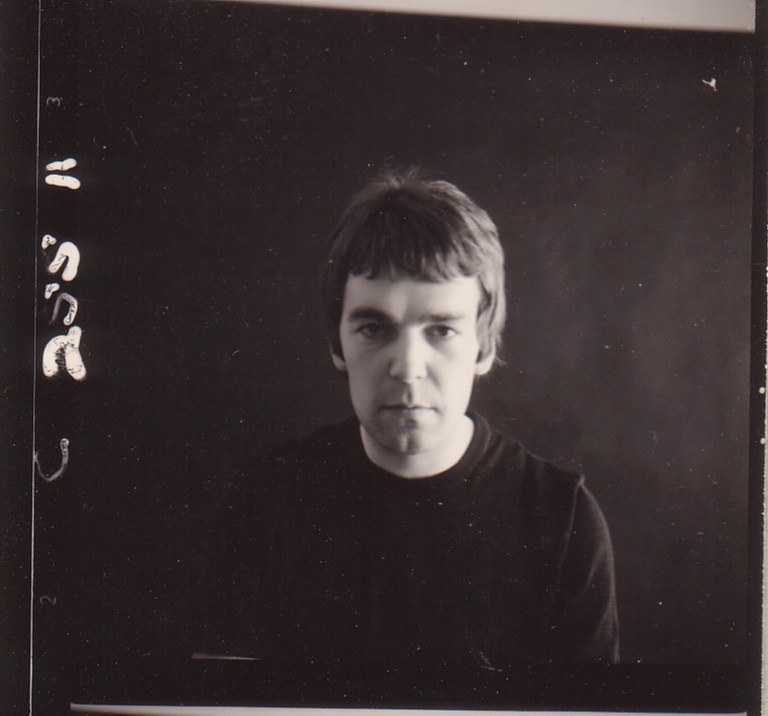

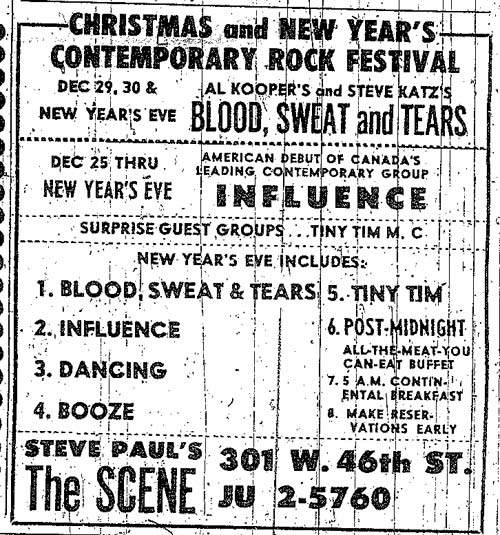

Andrew Keiller, South Africa, 1965 (photo courtesy of Andrew Keiller)

You must be thrilled that with the first CD release of Influence’s album by Pacemaker in Canada, the public will finally get to hear this great band? Why do you think Influence were so unique?

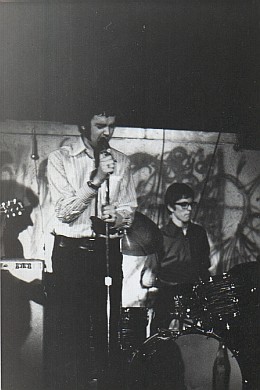

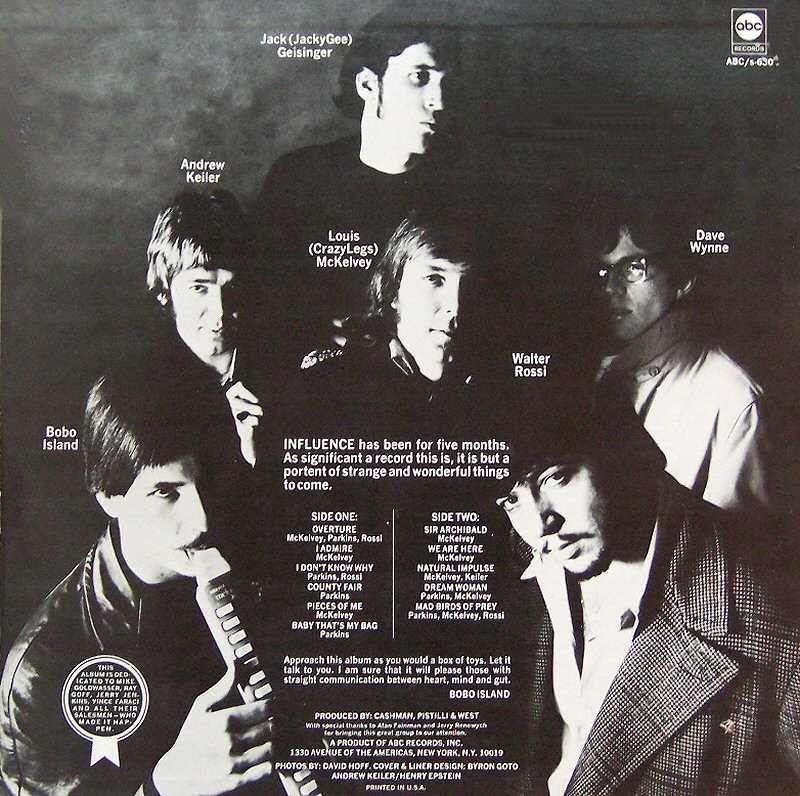

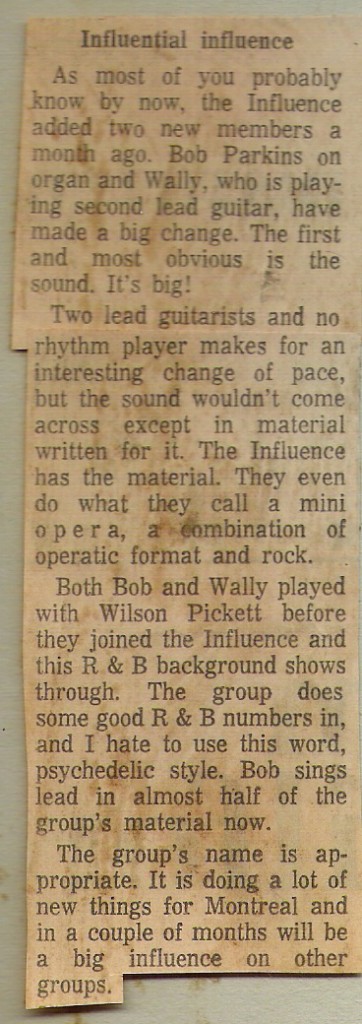

At the time it was a six-piece with two lead guitars and a keyboard so we effectively had three lead instruments and two lead vocalists and we were playing mainly original material plus a bit of humour and satire. We even had dance routines as well, which was like the humour side. We were pretty unusual at the time, even in those days.

Louis had a pretty much traditional British rock ‘n’ roll type background – you know Chuck Berry and Little Richard and people like that. Wally (Walter Rossi) was much funkier, more of a soul-type guitar player – you know Wilson Pickett, Booker T and people like that, so we had two different backgrounds.

Also Louis had a real sense of English prose as well, poetry and stuff like that. The influences from the two song-writers were quite different.

Influence started out as a quartet comprising yourself on lead vocals, Louis McKelvey on lead guitar; Jack Geisinger on bass and Dave Wynne on drums. You’d met Louis in Johannesburg in late 1965 and recorded together as The Upsetters. It’s quite astonishing that you should cross paths again on the other side of the world two years later purely by chance?

After returning from South Africa I did meet Louis briefly in London. We’d been corresponding and I went up to London and spent a few days with him in Notting Hill in some crappy bedsit. He was starting a band and I didn’t think it was going to go anywhere so I split and decided to go to Canada.

Just by chance, I think Louis went to Vancouver first and I contacted him after seeing him on a Montreal TV show. We met up at the Record Cave, which was a really good record shop in Montreal. He said he wanted to start a power trio with a vocalist and that’s what he did. At the time I think he was with a band called The Haunted [Ed: It was Our Generation] and Dave Wynne was the drummer, so they both split together.

It is probably fair to say that the addition of organist/singer Bob Parkins and second lead guitarist Walter Rossi transformed the band and raised its game. What do you think they brought to the group?

Bob Parkins and Wally were actually in a band called The Soul Mates with the bass player Jack Geisinger, so that’s how they got to meet us. They brought a much funkier sound to a lot of the songs.

[Parkins] had an interest in satire, so it was a bit of a vehicle for him and Wally just wanted to make everything funkier. When we had been playing as a four-piece with effectively one lead instrument and then suddenly you’ve got two lead instruments and an electric piano or Hammond B3, the sound was monstrous, especially with two people singing and back-up vocals as well.

He [Bob] was probably the most musical, knowledgeable guy in the band. He could play sax as well as keyboards although he never played it in the band. [But] he could be an embarrassment sometimes. We got into some terrible arguments in restaurants; he would cause a scene. I liked him; I thought he was a real mysterious sort of guy.

[Jack] was a tremendous bass player and a good singer as well. His big ambition was to be exactly like Johnny Rivers. He wanted to be just like that, singing nightclubs and doing standards.

Although we still did our early stuff that Louis had written for the quartet, [the songs] were completely re-arranged and the sound would knock your head off. It was really good.

In Montreal all they wanted to hear was soul music and whatever was in the hit parade… so we said, “stuff this, let’s go to Toronto” and we immediately had a huge audience. We were amazed that we were popular almost as soon as we got there.

Your singing was very different to Bob’s. Who inspired you as a singer and how did you decide who would sing lead on what tracks?

I came from the English background and Bob had a really authentic soul sound because he’d been playing that kind of music for a long time.

I was inspired by Sam Cooke, Gene Vincent, even Frankie Laine. But when I first saw Mick Jagger, he was the first person that I’d seen singing R&B with a cockney accent; he didn’t make any attempt to change it at all. I thought that was really inspiring that he didn’t care and he had a huge influence.

[In Influence] I would sing most of the stuff that Louis wrote; Bob would sing his own stuff and where we’d all collaborated we might do one or two verses each or we’d do a harmony each between us. That’s how it worked.

Were there any tracks that were recorded but weren’t included on the album?

We had a lot of material that didn’t get on there. We were hoping to do a live album. We did get a concert recorded when we played at the Electric Theatre in Chicago. They had a studio like suspended from the middle of the ceiling. They recorded and gave us the tape but it ended up with our manager Bernie Cougleman and that was the end of that.

It had a lot of stuff on it that we probably would have put on the next album. The mini opera [“Mad Birds of Prey”] was actually much longer on stage than on the record. There was a lot more to it. Bob would have included a lot of things from the current political scene.

I really love two tracks in particular that you sing lead on – “Natural Impulse” and “Pieces of Me”. You co-wrote the former with Louis. What were these two songs about?

“Natural Impulse” – I sat around noodling one afternoon and I put a few words together. I showed it to Louis; I think I had about half a song and he came up with the arrangement for the middle section because there’s a time change. Some of it is about superstitions – you know if a hunchback crosses your path, it is bad luck. That was a line that was in the middle.

When we came to record it, I had trouble with that middle section and so Bob actually sang that middle eight. He did that but normally on stage I’d do the whole thing.

Besides your singing, you also brought your artistic skills to the band’s stage set. Tell me about that.

The dance part of it – Bob and I dreamed up as dance steps. We got a huge reaction from that but the stuff was simple to come up with and it was a lot of fun.

I did some pop-art style artwork for the band. I did a drum skin with Elvis’ face and I did a big portrait of Mandrake the magician, the cartoon character, which was mounted on the front of the Hammond B3.

When we were recording at ABC, I spent some time in the art studio working on ideas for the LP sleeve. I painted Wally’s Stratocaster, the pale blue one, which got stolen unfortunately.

The album was a minor US hit and you toured the US Midwest with several notable acts. What are your memories of this period?

We had this big argument just after we finished recording and we had played The Scene. I’ve got a feeling that it had something to do with whether we should go with this manager or that manager and I was getting a big twitchy.

[I left the band and] worked in a drafting agency in Philadelphia because my wife’s relations were there. We stayed with them and I did some freelance work and it was really great.

But I got this nasty letter from Bernie telling me that he was going to tell the US authorities that I was working there illegally. He wanted me back in the band because I was under contract. I was gone for a month or four or five or six weeks. I spoke to Wally and he said, “Look, it’s a lot cooler. Bernie’s given us some money every week. It’s bugger all but it’s something; It’s food money”.

On that basis I went back to Toronto and re-joined the band. When they came up with the tour to go to Chicago I thought, “Great, I really want to go to Chicago”.

We had equal billing with Steppenwolf. We played in Chicago and Detroit, where we were second down from Procol Harum, who were big at the time but they were really snobs. They wouldn’t talk to you. I don’t know why.

We actually had another gig booked up on that tour in Louisville, Kentucky. I think Bernie chickened out on that and we didn’t go.

[I remember] we met the Chicago Plaster Casters and didn’t realise what they did until much later when they turned up in Rolling Stone.

Seeing a lot of the States but not having much money to enjoy it was a bit of nuisance and I was on the road with the wife and two kids. The youngest son was only six months old at the time.

In May 1968, you left the band and briefly returned to the UK before emigrating to Australia in 1971 where you’ve lived ever since. What prompted you to depart?

We just had no money. That was the thing and we had such terrible management. Bernie couldn’t think big enough. He was trying to juggle us with his legal business. We had a whole package and could have done really well. We did meet people in the US who wanted to do stuff with us but weren’t able to follow up on it because Bernie didn’t have much imagination.

We had a really crappy contract with him where he was getting 40% or something. He would have screwed us into the ground even more I think if we had managed to get away from him and gone with somebody else.

The people we met when we were recording at ABC they could really have helped us. There was a guy called Joe Zeto who was based in Hollywood and then there was a girl who was a co-producer at ABC and she wanted to take over the management as well.

We had a big band meeting and of course three of them wanted to go with her and three wanted to stay [with Bernie]. It didn’t really work but it’s a shame. The whole scene is littered with stories like that, isn’t it?

When I went back to England, I worked for British Aerospace as an illustrator working on the Concord. I wasn’t making enough money and we were living on our savings so I got a job in Australia with the domestic airline doing technical publications and I stayed with them for 12 years. Then I was freelancing until 1996 when I decided to work on these race cars that we are doing now. I am still doing that.

Looking back at Influence, why don’t you think you achieved more in the brief time that you had together.

It had something to do with the management situation. That’s why we weren’t able to follow up on a lot of leads we got, which was a shame.

We all really want to go to the West Coast. Everyone we met in America said, “You got to go to San Francisco; you got to go to L.A.” We just didn’t have the finances to make that trip.

We had a really good scene going. We were kind of different at the time. I am sure we could have done really well. We would have had a much bigger spread of audience I think.

- Andy Keiller today (photo courtesy of Andy Keiller)

Thanks Andy for giving up your time to answer my questions.

Nick Warburton is a UK-based freelance writer, who has written for Shindig, Record Collector, the Garage Hangover website, Vernon Joynson’s book series and Richard Morton Jack’s, Endless Trip.

Copyright © Andy Keiller and Nick Warburton, 2013, All Rights Reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced without the permission of the authors.